Dear Artist,

When Mark Landis was a boy, his well-to-do parents would take him travelling in Europe and leave him alone in their hotel room while dining out in the evenings. Young Mark passed the time by watching old movies and drawing. He would copy from art catalogues collected from museums visited during the day. “It’s reassuring,” he said.

Over the years Mark honed a variety of techniques for getting things to look just right. He’d place a sheet of paper over a catalogue image, then flip the paper back and forth while making short marks in pencil. He calls it his Memory Trick. “You remember it long enough to get it down,” he says. “Then you forget it.” A doctor who’d treated Mark for schizophrenia told him his ability was exceptional. Mark says it never occurred to him that not everyone could do it.

In 2008, at the age of 53, Mark Landis was discovered as one of the most prolific forgers in modern history, duping over 60 American museums over a 30-year period with donations of his fakes. Mark gave away his imitation Picassos, Watteaus, Cassatts, Averys, Magrittes, Schieles, Signacs, Daumiers and even a Charles Shultz. He made multiples because, as he says, in repetition his work improved. Mark bought supplies from the local Hobby Lobby in his hometown of Laurel, Mississippi and made his donations while impersonating the grieving brother of an art collector or a Jesuit Priest fashioned after the fictional detective character Father Brown. Mark, though admitting he’s a bit mischievous, says he did it all in the name of philanthropy.

Many artists can attest to the reassurance that arises when something familiar, and familiarly good, appears before them on the easel. Perhaps pulling off a Schiele or a Shultz is a short cut to a satisfied feeling of achievement. In Leonardo’s time, apprentices were expected to copy his originals as he painted them. The Prado Museum even keeps a slightly plumper Mona Lisa in their vault. More recently, artists shun mimicry (publicly) and adhere (or attest) to sweating out originals, although many learners will go through the paces of copying in order to understand the nature of materials and technique. Mark never set out to be an artist. He says the art world characters in old movies that seemed to be getting the kindest attention were the philanthropists. Sure enough, the curators loved him — until discovering his deception. Even so, in 2012 the DAAP Galleries at the University of Cincinnati mounted an exhibition of Mark Landis’ forgeries. The artist was in attendance.

Sincerely,

Sara

PS: “I have no delusions about being any sort of great artist. I decided to be a philanthropist.” (Mark Landis)

“The criminal is the creative artist; the detective only the critic.” (G. K. Chesterton, The Innocence of Father Brown, 1911)

Esoterica: Mark’s techniques have included cutting wooden boards into replica sizes, distressing paper with instant coffee and photocopying catalogue images enlarged to the size of the originals, which he would then go over with acrylic medium to simulate brushwork. “What I do with things like this is, I do one that I can think of as a master,” says Mark. “Then I run them off on my computer and go over them with some chalk and colored pencils and stuff. Before you run them through the computer, you stain the paper first, otherwise the ink will bleed. And then it looks fine. It looks like a million dollars. Or half a million, I suppose.”

ART AND CRAFT: Official Theatrical Trailer

[fbcomments url=”http://clicks.robertgenn.com/gift-horse.php”]

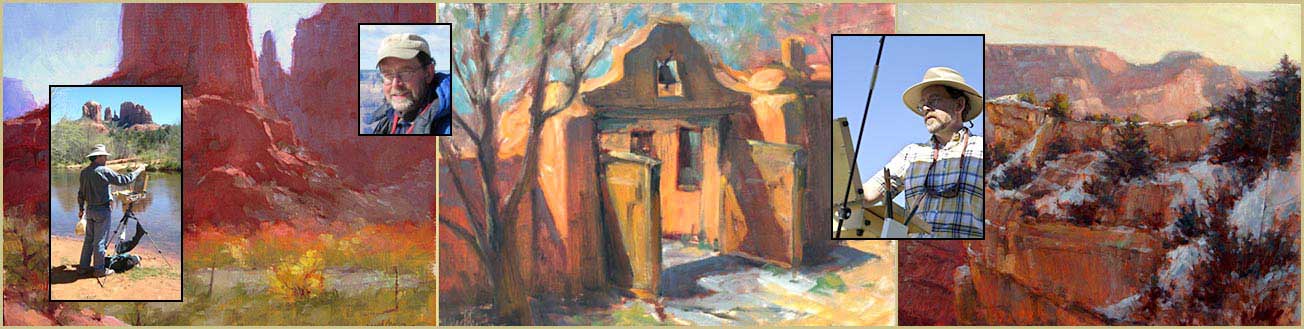

Featured Workshop: Michael Chesley Johnson

You may be interested to know that artists from every state in the USA, every province in Canada, and at least 115 countries worldwide have visited these pages since January 1, 2013.

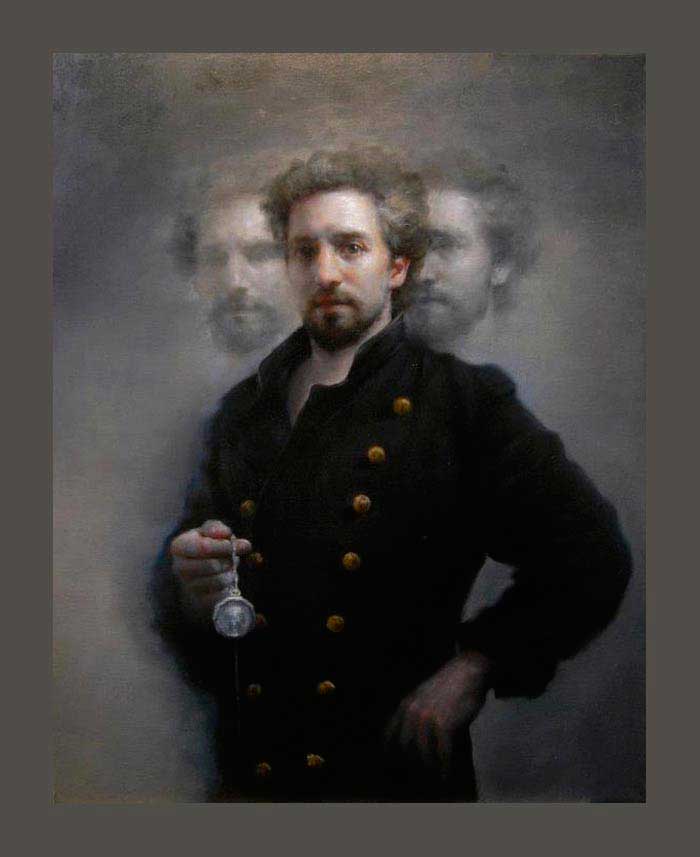

untitled original oil painting by Maria Kreyn, New York, NY, USA |