Dear Artist,

This morning Hanneke Spruijt-Teunissen of the Netherlands wrote, “As someone who gets her artistic schooling from evening and weekend courses — how much time did you spend on perspective as a student? How thoroughly are academically trained realistic painters grounded in the laws of visual perspective? Is the absence of this knowledge one of the factors preventing amateurs from attaining the quality of professionals?”

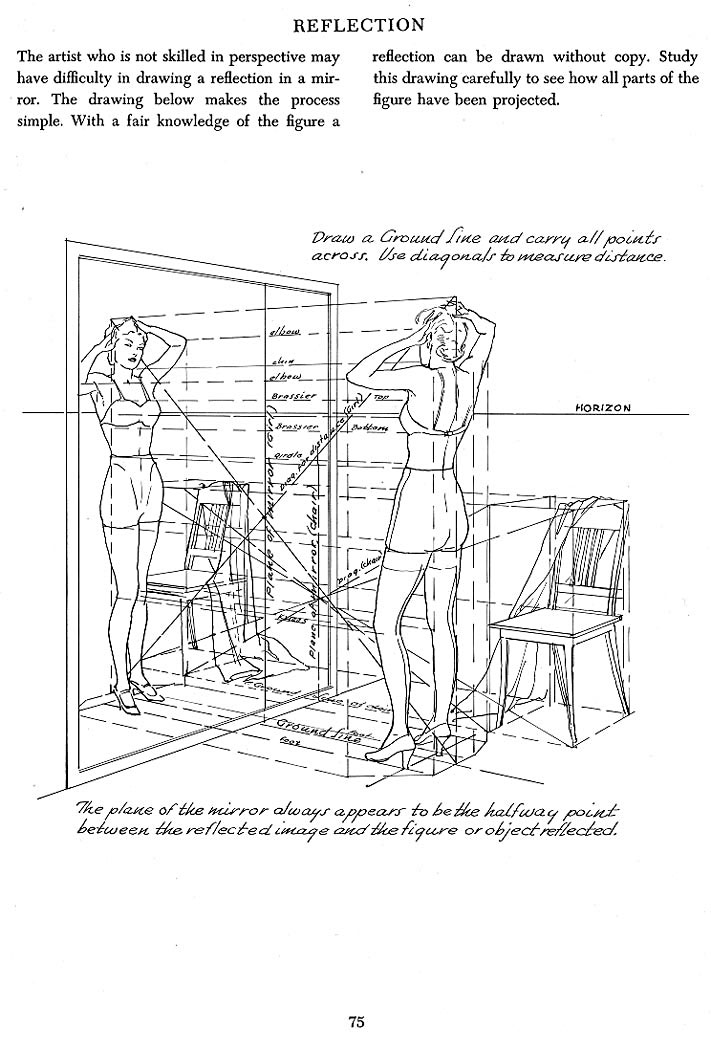

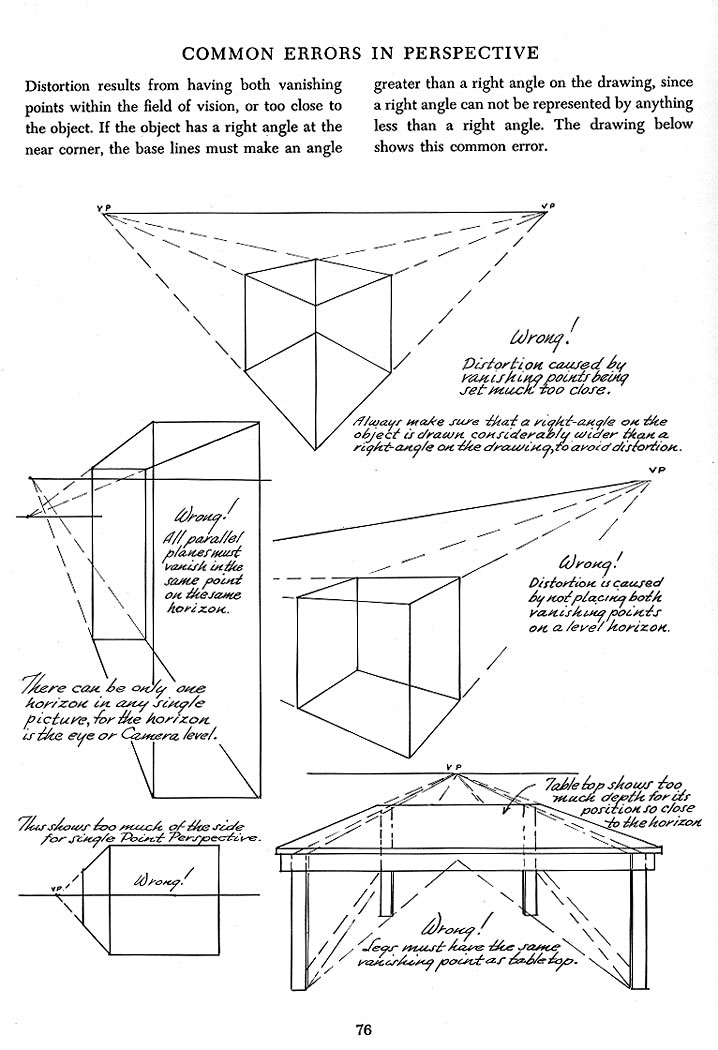

Thanks, Hanneke. It seems to me that perspective is tucked away in some of our pockets and taken for granted. When I was a kid, my dad, a stickler for proper drawing, actually took me into city streets and had me look past a transparent ruler to find horizon lines and vanishing points. Christmas also brought those marvelous books by Andrew Loomis. In her email Hanneke pointed out where you can find the Loomis books online. Sure enough, like visiting old friends — there were those well-remembered pages. “Andrew Loomis lives,” I shouted around the studio, and things got out of hand for a while. Loomis’ classic illustrations are still the clearest. I’ve asked webmaster Andrew (not Loomis) to put up some of them. See below.

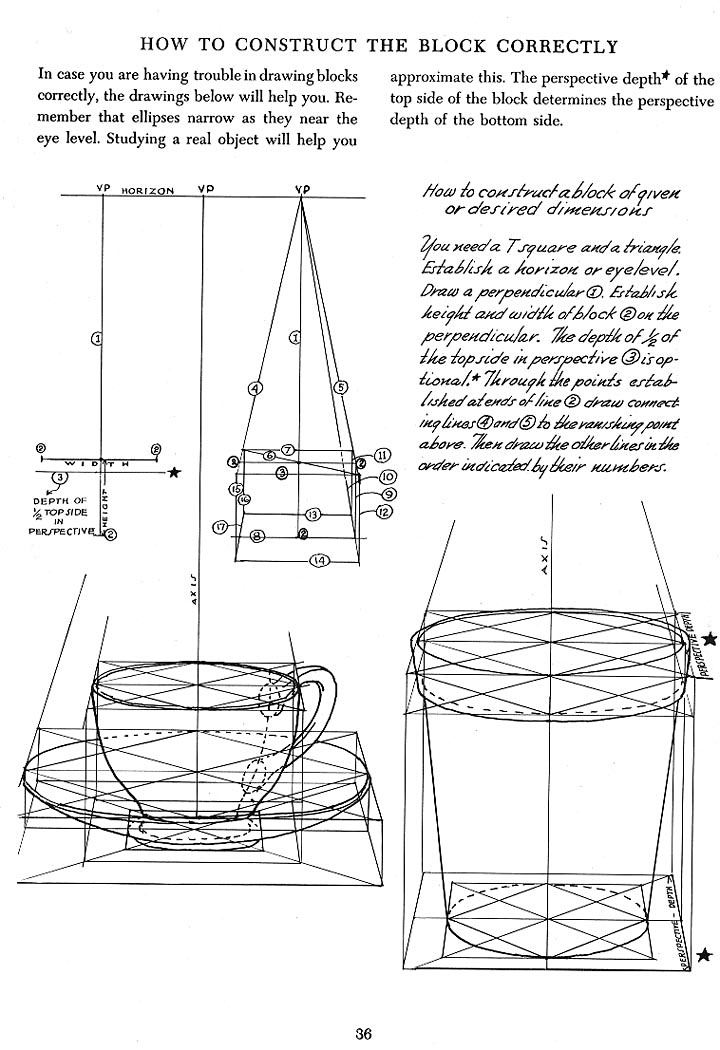

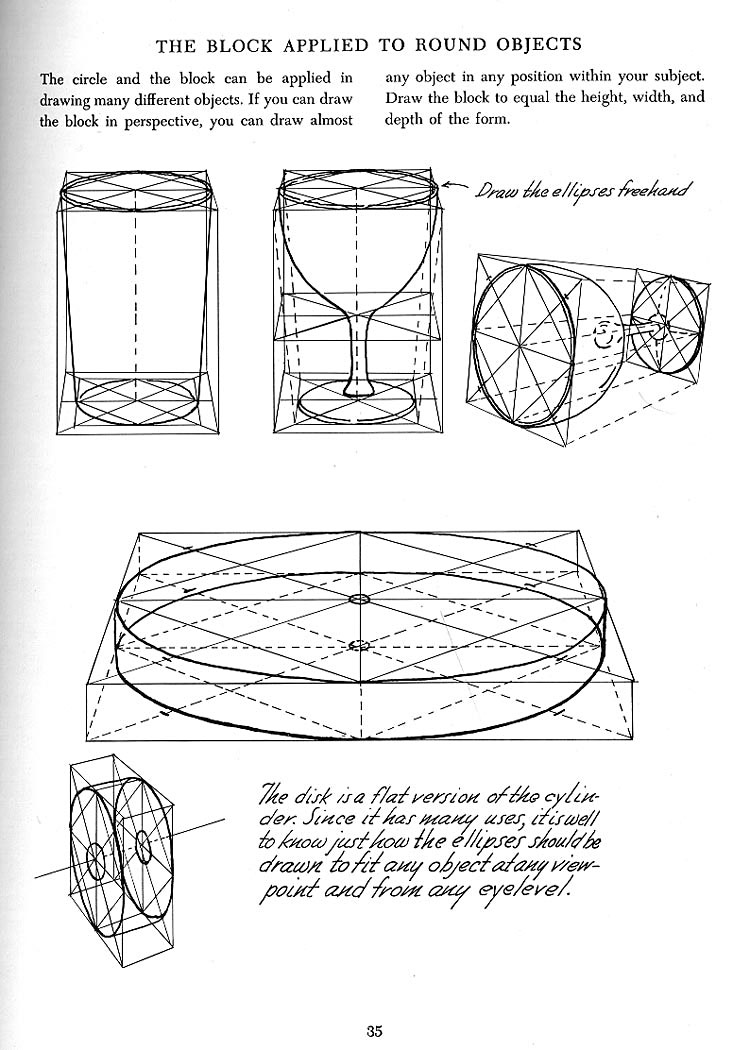

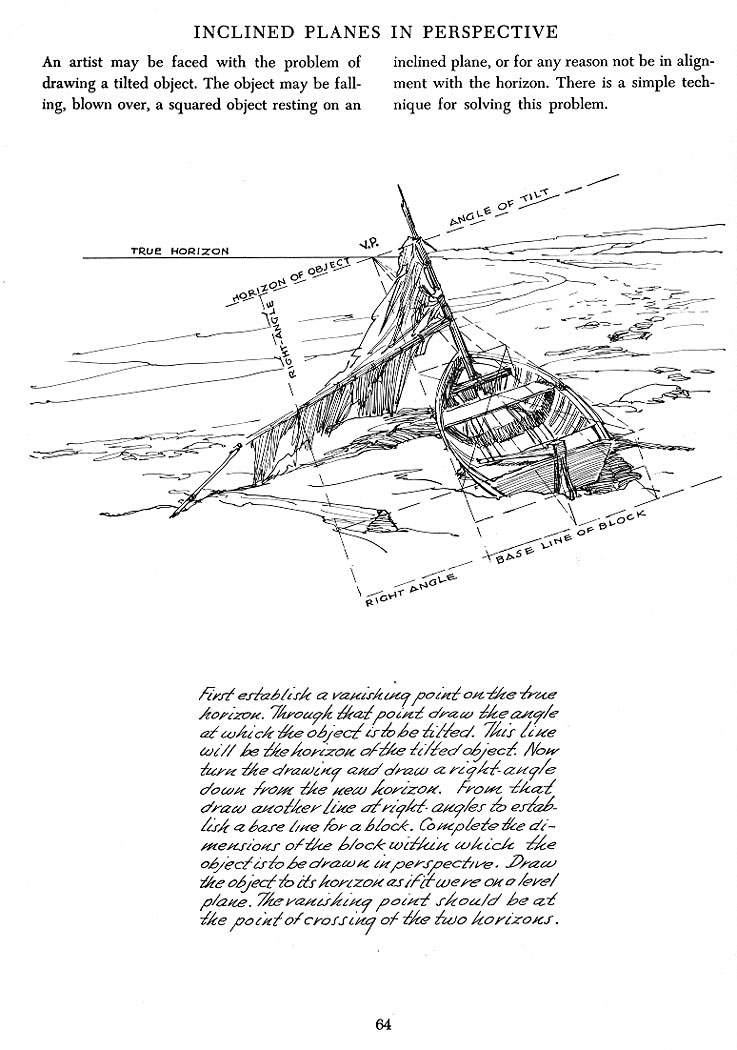

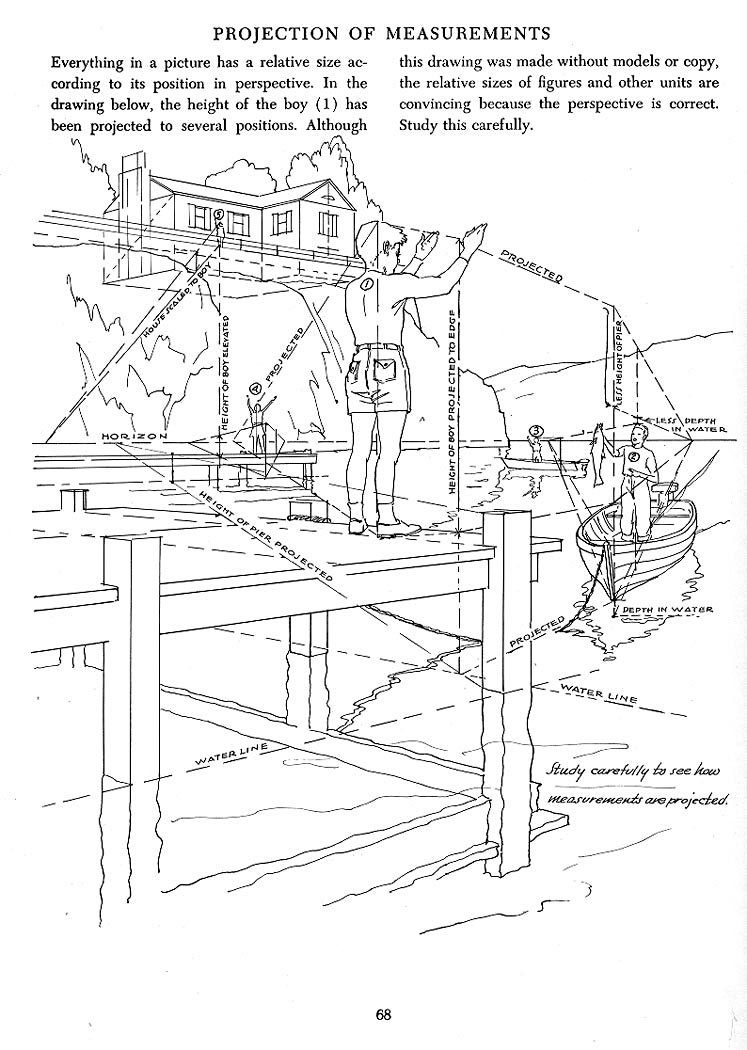

An understanding of perspective is achieved with observation, practice and a quality handbook. With the system of “blocking,” Loomis methodically shows examples of perspective — from simple and obvious conceptions to the most complex and difficult. You need to learn correct block construction. Blocks make it easier to project perspective on varied surfaces, as well as repeating designs on flat, curved and even reflective surfaces. He gives techniques for scaling perspective from interior and exterior elevations as well as equal and unequal spacing of solids in perspective. The projection of figures on level and inclined planes is covered, as well as the use of diagonals in single and double-point perspective. Projection by measurement might catch your interest — or perhaps perspective within the human figure. There’s plenty of good stuff to learn. Loomis also describes the common errors in perspective — and there are plenty. Yes, Hanneke, this knowledge is valuable. And when you study it and know it well and put it deep into your pockets, you will begin to see examples every day of work by people who, for one reason or another, can’t be bothered.

Best regards,

Robert

PS: “If you intend to make a living at drawing, by all means learn these things now, and do not have them bothering you and your work for the rest of your life.” (Andrew Loomis 1892-1959)

Esoterica: One of the most effective figurative ploys is to “hang” the eyes of human or other subjects along a common horizon line. Thus the viewer can also be deftly placed in a sitting, standing, or other position. Apart from a degree of correctness, a sense of presence is created. “Eye contact” can also be made in this way with the “eyes” of inanimate objects — autos, mandelas, totems, even flowers. Eye-to-eye finds visual truth.

Successful Drawing and other books by Andrew Loomis are available used from Amazon.com.

Alex Ligget’s website: Save Loomis is offering, for free, several of Andrew Loomis’ instruction books. They include: Successful Drawing, Fun With a Pencil, Figure drawing for all it’s worth, Drawing the Head & Hands andThe Eye of the Painter (black and white). Also, Peter Levius is offering Creative Illustration by Andrew Loomis free on his website: Human Anatomy Pictures for Artists Online

Successful Drawing Plates by Andrew Loomis

Seeing the way it works

by Mary Moquin, Sandy Neck, Cape Cod, USA

I enjoyed looking at the images of Andrew Loomis. I often have students with perspective difficulties and thought it might be a good book to have on hand to show, but did you realize that it is available on Amazon for $500? A bit steep. The science behind perspective is quite useful information. Nothing replaces just visually seeing the way perspective works in nature and copying those angles into your painting. A lot simpler than studying a lot of theory. However, when our eyes fail us, there is always the science to bail us out.

www.capecodfineartist.com

(RG note) Thanks, Mary. There’s an international collectorship for Loomis books. They go for higher prices every year. The event has sent elderly artists rummaging in their dusty bookshelves. The books used to be a dime a dozen. For the time being some enthusiastic collectors have them online. I somehow think Andrew Loomis would approve of this. Maybe his heirs aren’t so happy. He made those books because he found people needed to know this stuff.

No mention of perspective

by William Lathrop, Chicago, IL, USA

In the artists I study, Richard Schmid in particular, the goal in seeing is to reduce everything to color shapes. Looking at what is before you and simply finding all the shapes and putting them on the canvas in the right shape, the right place, the right color and the right value with the right edge. This process seems to by-pass the knowledge of perspective. In reading Schmid’s book, I can’t recall any passage on perspective. I’m curious how you reconcile this issue or approach to painting.

(RG note) Thanks, William. It’s the old classic one-two thinking again. Painters like Richard Schmid have put so much perspective in their pocket that it becomes accurate, automatic and taken for granted. Or they may use projectors which pretty well takes the sweat out of perspective.

Perspective video instruction

by Dorothy Lack, Albuquerque, NM, USA

I teach 6th-8th grade future artists in a public school in Albuquerque, NM. I stress the need for perspective by using a videotape on Basic Perspective that is available from Crystal Productions. It is very straightforward and covers 1-, 2-, and 3-pt. perspective. We use the information to draw fantasy boxes and landscapes — and it even helps improve their still-life and lettering.

(RG note) Thanks, Dorothy. This is excellent material for children of all ages. Teaching art is also available online.

Further videos on perspective

by Virginia Wieringa, Grand Rapids, MI, USA

Here are two of my favorite ways of making perspective accessible. Masters of Illusion is a video by James Burke that cleverly traces the development of our Western method of perspective to the Renaissance (of course, other cultures have their own ways of communicating distance). For young kids, it’s hard to beat Commander Mark (Mark Kistler) and the Imagination Station. Creating the illusion of 3D in 2D is an amazing and powerful skill.

Perspective taught early

by June Szueber, Perris, CA,USA

What a wonderful wealth of information in Loomis’ books! My well-used, well-worn copy of Head and Hands has served me well. As to the perspective I wholly agree. I have recently begun to teach linear perspective in the 3rd grade. I find if I wait until later the students have such a fear of it built up that it is hard to get through to them. Adults consider it an impossibility. This year I am beginning in the 1st grade with a group of trees at various distances and ending at the Junior high level with the new circular perspective.

(RG note) Thanks, June. Another unique and valuable perspective guy is Dick Termes; his interesting ideas and applications of perspective can also be had from his site for $10.

Is perspective innate?

by Valerie Hallford, Kelowna, BC, Canada

Do you think that perspective can be innate, (possibly genetic), not particularly tied to training? I do not mean by this that it cannot be “learned.” My mother was blind in one eye from an accident when she was five years old, yet her perspective was uncannily perfect! I have had little training, but I have been able to draw in perspective with considerable accuracy since childhood. (And I have driven more than one printer crazy with my insistence that a word be moved a 64th of an inch!) One of my daughters has the same gift (of drawing accurately), evident from a very early age. One of my grandsons (not the child of that daughter) appears to have “inherited” the same ability, although not to the same degree. As he has ambitions to become an architect like my grandfather, I trust that with proper training he will acquire the skill.

(RG note) Thanks, Valerie. Interesting question. As perspective comes easily to some and reluctantly to others you might think so. Accurate drawing is related to right brain dominance and in my experience those with “automatic” perspective are from this camp. Right brain dominance seems to run in families. It’s a bit of a mystery. It seems that learning perspective is like learning a language — quite natural when started in youth, more difficult for older people. On another note, never underestimate the value of looking at things with one eye.

Identical twins paint same picture

by Leonard Niles, Lincolnshire, England

If someone asked me about perspective and how I achieve it, I would be absolutely gob struck; I seriously would not know what to tell them. It would be like asking a Centipede which leg he was going to put forward next and if he had to think about it, he would sure as hell finish up on his back. The most marvellous demonstration of some painters’ natural ability to perceive things in perfect perspective was no better demonstrated than on British television in front of thousands of viewers. Two sisters (identical twins) whose chosen subject was horses (there was nothing unusual about it, or so I thought), were to paint on the same canvas, and they both started at opposite ends without any prior consultation. When both parts of the picture were interacted there were no obvious signs of demarcation. The two halves matched perfectly in perspective, symmetry, light and shade, colour tone; and the horse itself was in perfect proportion! I never cease to wonder at the capacity of human potential.

Choice is strength

by Coulter Watt, Quakertown, PA, USA

To this day I have and still use a 9 x 12 inch paperback booklet that I’ve had since I was a child. It illustrates blocking in objects on a plane. I use this fundamental process to this day, although to a lesser degree only because I’ve become more adept at visualizing the end result and can skip much of the “wire frame” drawing to define space on the canvas, but, not in my mind.

When I see paintings where the eye level is that of the tabletop and the objects are profiles it makes me wonder if the creator can actually draw and define space. I feel held off by the design trickery and it looks like an illustration. Where as I’m drawn into a picture when I can see the table top, the depth of perspective draws my eye into the space and forces my eye to navigate around the spatial illusion. This allows me to paint light flowing across the surface and around objects which sets up the play of lights and darks, creating a play of contrast and separation. That light path also directs the eye around the painting, from object to object.

The great value of a solid knowledge of perspective is learning the structure of illusions, the skill of making objects appear solidly planted, as though they really own the space they occupy on the painting surface. My booklet is worn, tattered and falling apart yet treasured.

Once you know the rules of perspective it is the painter’s choice to use the techniques or disregard them as a matter of intelligent design and style, but there will be no struggle to achieve the desired effect. Choice is strength. Having choice is also freedom.

Limitations to art school

by Joe Jahn, Denmark

At art school I expected to learn something. The only thing I learned was that each instructor was dead set against realist art. It was not art. It was old fashioned and not worth teaching. Obviously they learned that from their instructors. They taught nothing, just watched you paint and held an occasional critique. So they didn’t teach color theory, perspective, color mixing, developing the artist’s eye, nothing. The 4 years I spent in various art schools was, from a technical point of view, worthless. God bless you if you find a good art teacher these days, especially if you wish to be old fashioned and paint, say, landscapes. Everything I learned, I learned through books and other artists. I spent 10 years painting before I dared have my first show. And I found that I knew more about art history and the basics of good painting than 80% of the so-called art teachers. It’s my experience that all good art is self-taught. Whether realist or abstract. And books are the gold mine of technical info on the subject of materials and their interaction.

Pay attention in art school

by John Ferrie, Vancouver, BC, Canada

When I was a young art student, I remember thinking I wanted to set the art world on fire. I wanted to and did have wild opening shows. I dressed like an art student, did weird things to my hair and listened to loud and unusual music. I went to shows and studied artists that had profound and bizarre works. I thought it was all so cutting edge. In school, often things came to a grinding halt, especially when it came to my foundation year and we studied perspective drawing. We would sit and draw Styrofoam balls, crumpled pieces of paper, drapery and all sorts of things that I literally thought would suck the life out of me. Once in a blue moon we would be allowed out in the hallway to draw the perspective of the hall. I usually just went for coffee when the instructor was not looking. These classes would often be six hours long and were dry as burnt toast. That being said…

These days I am always trying new ways to break through with my voice as an artist; I am always trying to better my work. I have found the very best thing is to recall on these foundation lessons and apply basic rules of perspective to my work. I am pulling out my old perspective drawing textbooks from art school and re-reading what I forgot or never paid attention to in the first place. Applying these teachings to my painting has enabled my work to pop and it gives me a whole new sense of myself. I am sure my old instructors would be laughing at me now.

Learning perspective by teaching it

by Susan Easton Burns, Douglasville, Georgia, USA

I worked as a detailer, drawing elevations and floor plans (construction drawings) for years, and had no need to learn perspective until I was promoted to a designer. I really didn’t have a grasp on perspective well enough until I decided to teach it. That was the turning point for me. I was learning every day as I taught it in the interior design department of an art school. It is all done on computer now, but I agree with Milton Glazer when he says there is a valuable step in every creation when pencil hits the paper. Many students that come out of design schools only knowing the computer are missing a critical developmental design step. Your brain is figuring things out while your hand helps you to visualize. I wish I had taught perspective much earlier. It gets you involved and unmistakably attached to the surface you are drawing on. Everything we draw or paint has perspective in it.

Don’t be a slave to perspective

by Ron Gang, Kibbutz Urim, Israel

When I was a child my father showed me how to do 1 and 2-point perspective with a ruler. I’ll never forget how amazed and pleased I was how easily I could produce drawings with illusionary depth with this technique. Later on, in grade 6 at King Edward Public School in Toronto, my blessed art teacher Miss Edna Goodwill (this is probably 1961) taught me further refinements in this technique. I wonder if this wonderful lady is still around. She taught me many things that a quarter of a century later I didn’t get in art college. Anybody out there knew her? Today I paint mainly plein air, yet I think that this early grounding in perspective really paid off. I remember trying to show my fellow students in art school how to do perspective, which seemed ridiculously simple to me, yet so many of them just couldn’t get it. Having said this, we have to know the laws in order to properly break them, and “perspective” is but one scheme of things, whereas there is perspective of colours (warms up front, cools in the distance), and other senses of space such as that which Cezanne developed, cubism, etc. So we shouldn’t necessarily be dogmatic slaves to linear perspective, yet it is definitely important to understand it.

Creating the illusion of distance

by William Band, Georgetown, Ontario, Canada

Perspective is the key to doing art. Since artists create visual shapes and patterns on a flat surface, nothing can be more convincing than the use of perspective to create an illusion of depth. Understanding and knowing where the vanishing point should be will make or break the value of the image. At present I am teaching perspective to students that are going in the commercial direction. They must understand what to look for while using the computer. My painting students must learn the rules in drawing and perspective. It is an absolute must even for the abstract artist to learn the rules before perfecting their own personal styles. I just got back from Scotland, and I am about to draw up many images of the old streets and some castles. I see the buildings as large shoeboxes all heading down to a fine point on the horizon. All detail of the windows as they get farther from the viewer becomes just a brush stroke, but must also be proportionately narrower to create the illusion of distance. Then there is the atmospheric perspective. I am once again thinking about the landscapes in Scotland, with the blue hills in the distance and the vibrant purple heather and detail in the foreground. Total depth and richness of colour that start to fade into the mist in the distance.

‘Amateur’ and ‘professional’

by Corinna Taylor, Chicago, USA

“Amateur” and “professional” as mentioned by Hanneke are used far too often to describe quality. This is nonsense. An amateur can be just as skilled as a professional. An amateur is someone who creates art out of love while a professional does it for money, a matter of choice and intention, not talent. In fact, an amateur may actually produce better work because she doesn’t have clients dictating to her.

Artists travelling abroad

by Paul Paquette, Vancouver, BC, Canada

I read with interest the news that your daughter is working in Paris. I’ve often thought about how wonderful it would be to take a year or two to work in Europe. However I find that I have some hesitation. After spending years building up a stable income selling my art in British Columbia by having established good working relationships with galleries here, I am reluctant — or should I say fearful — of packing up my bags and heading overseas for anything more than a vacation. Do you have any advice (or past experiences) concerning the logistical and practical problems of working over there while maintaining good relationships with galleries over here. I guess what I’m asking is how realistic is it to live and work half a world away from your home base and all its familiar contacts and resources?

(RG note) Thanks, Paul. I once went to Europe for a year and a half with a guaranteed income from one of my home dealers. Deliveries back became spotty and so were the cheques after a while. Shorter trips are no problem and I’m afraid it’s chronic and part of our family tradition to always be going somewhere to recharge our batteries.

(Sara Genn note) Hi Paul, What is it that is most important to you as an artist — your stable income in one region (which is a huge accomplishment to be sure), or broader experiences that may inform your development? Does your muse urge you to go out and live in the world from another perspective? Not all artists need or desire this… but for those of us who do… it is simply imperative that we move our studios every once in a while. While I maintain an income with my galleries, I really don’t factor paycheques into my sojourns; my sojourns are simply for me and necessary “points” in my artistic journey. I line up my ducks, and go. By going I have learned how little I really need, what I am capable of, artistically and otherwise, and that I want to do more. No guarantees, but always, always inspiration. Yes, I sometimes supply my galleries when I am away; I show in my Canadian galleries even though I now live in New York. To my galleries, moving around keeps my trajectory interesting and my growth in full bloom. While I understand that you would never want to sacrifice your hard and long-earned position with your galleries in B.C., my advice to you is to determine what it is in your heart you wish to be and do as an artist. You know you can sell — if this was your goal, then you have achieved it — and may have farther you wish to go in your professional establishment, or in wandering the Earth being you. The good news is that I don’t think these aspirations are mutually exclusive.

Living with a copycat

by Rosalie Hein, Billings, MT, USA

Your letter Copy, right? hit a raw nerve. I had a partner in my studio the past 5-6 years. He has copied my work on a daily basis. He is a nice guy but can’t seem to have anything originate from himself. He started painting with my style, color palette, etc. I have come into the studio at times and he has his nose up to my paint figuring out how I did it. He has bought his way into the local gallery by giving huge donations (his wife has a lot of money). I know 5-6 years of putting up with it! What was I thinking of? I finally moved out of the studio after building one at home. I know how petty I am to be thinking, let’s see how he does now that I am not there to copy everything from. Seriously, I am upset to the point that it has hindered my own desire to paint. Have any ideas how to get over my jealousy and hurt? I know I have to just go on and not worry about what has and is happening.

(RG note) Thanks, Rosalie. You have to wash that man right out of your life. You also owe it to him so he can be outside of your aura. He needs to be set free to find his own style and feel better about himself. You too need to find the joy and value of progress in solitude. In our business, there is something to be said for isolation. Your situation is a lot more common than one might think. Time heals.

Bartering watercolour painting |

You may be interested to know that artists from every state in the USA, every province in Canada, and at least 105 countries worldwide have visited these pages since January 1, 2005.

That includes Helen Scott of New Bern, NC, USA who wrote, “Everything ‘hangs’ on well done perspective in paintings and drawings. If the artist does not understand perspective and how to see and use it, all the applications of paint and ink and pencil will not overcome the lack of good perspective.”

And also Mona Youssef of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada who wrote, “Painting realistically without knowing perspective will get you a lot of criticism.”

And also T. J Miles of Timonium, Maryland who wrote, “I have been a professional artist for approximately 5 or so years, and touch wood, continue to make a living and evolve each year. I currently split my time between my homes in Ireland and Spain. Since becoming a full time artist I have more time to travel, and find, in turn that my art is slowly, subconsciously changing as well. Living such a nomadic lifestyle, I don’t tend to get as much exposure to other artists as I would like to, so I very much welcome the input of you and your friends.”

And also Constance Cavan who wrote, “We finally moved from the San Francisco area to San Miguel de Allende, GTO, Mexico. I’ve been here just two weeks, but we have been planning this move since we bought this place last fall as a good place to live on a budget. Suddenly your letters are even more important to me — I am disconnected from where I lived and somehow, being in a really different kind of place, I am suddenly more in touch with myself. I am in sort of a “state of shock.” Your letters and their responses make a sort of universal connection for me that is emotionally touching and fulfilling.”

And also Jann Semkow who wrote, “As a visual art teacher of just awesome senior high school students I need to be a “jack of all trades” so to speak, and a magician of time and space as well. I strongly encourage my students to go to your site and to reflect and respond on its contents through a variety of means, including journaling and applied research.”