Dear Artist,

Subscriber Jack Monk writes, “Is visual art on its way out? Or is it just landscape painting that is the most dead of all art forms? Should it just be allowed to die or to reconstruct itself in some (as yet unimagined) new form?”

Thanks, Jack. After googling, “Is painting dead?” and coming up with 104 million results, I can report that painting — including landscape — appears to be alive and well as the beleaguered martyr to windy academic discussion, art world speculation and as the reject of conceptual art. Sassy New York curator Corinna Kirsch has even made a chart to track the ebb and flow of the medium’s demise and resurrection. “Nobody’s willing to go on the record saying it is finally, truly, and forever dead,” says Kirsch. “Instead, we get an in-crowd of critics attempting to knock down a straw man that nobody really believes in.” More importantly, while in Utah recently I pushed open the door of a regular-looking storefront at the edge of a main street shopping strip. Inside was a maze of temporary walls salon-hung with pine thickets, glowing mesas, plateaus and canyons, anointed peaks and silvery flats. Totemic sandstone formations vibrated in whisky strokes splashed with late, reflected light and local colour. Smaller works breathed their location’s authenticity: fast and fleshy plein-air beauties, timeless and immediate — covetable gems signed with new male and female names. From where I was standing, the painted landscape breathed and pulsed from gilded frames under dedicated, halogen spots.

When asked about painting’s future purpose, abstract and photorealistic painter of landscapes Gerhard Richter replied that contemporary painters have both a connection to the tradition of painting and the need to depart from it. “Questioning the medium,” says Richter, “is part of the job.” From the gallery, I took my hot cheeks out into the Great Basin’s winter afternoon. “So old, so new,” I thought. For artists, painting is a cosmos of exquisite pleasure and pain, with landscape but one dialect of an infinite language, one that’s perpetually and nobly evolving within her archaism. The pang to drag a hog-hair bright across a crisp weave of linen burbled from somewhere inside my pea coat. I tilted upward, past the horizon, toward Utah’s dry sky. I inhaled, “Long live landscape.”

Sincerely,

Sara

PS: “From today, painting is dead.” (Paul Delaroche, purportedly said after seeing the daguerreotype, the first successful photographic process, in 1839)

“The art of painting will survive and thrive because it is easy to do and difficult to do well. In my opinion, reports on the death of painting have been greatly exaggerated.” (Robert Genn, 2012)

Esoterica: Our connectedness to nature and our wish to commemorate life and our place in the universe compels us to describe our physical surroundings and, in doing so, ourselves. Landscape’s compositional and spiritual cues also contain the vital seeds of abstraction and beyond. If painting is our medium, then we are the medium for painting. Rather than being left to die, landscape is taking on its new (as yet unimagined) form through us. We are the new form. “Art,” said Gerhard Richter, “is the highest form of hope.”

[fbcomments url=”http://clicks.robertgenn.com/landscape.php”]

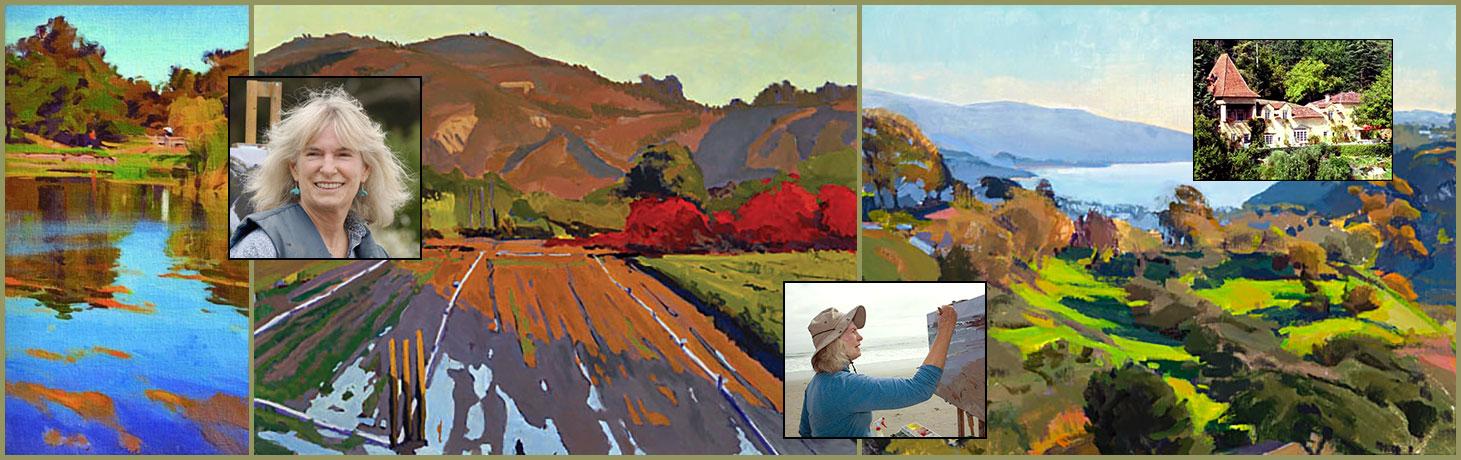

Featured Workshop: Marcia Burtt

You may be interested to know that artists from every state in the USA, every province in Canada, and at least 115 countries worldwide have visited these pages since January 1, 2013.

Bright fields beyond the town, St. Just acrylic on canvas 50 x 180 cm by Tom Henderson Smith, Saint Columb Major, Cornwall, UK |

Share.