Dear Artist,

“Bob’s minutiaescope,” named by friends, is a spade-like, homemade device with a remotely triggered digital camera that takes close-ups of stuff on the ground. For no particular reason apart from the idea that gardens, pathways, beaches and forest floors are loaded with patterns and natural designs not always appreciated until isolated in blow-up.

I’ve always admired the British oddball Edward Muybridge. Back in 1860, while in Texas, the poor chap got into a stagecoach accident. He hit his head and spent years in medical treatment. Later he got to know U.S. senator and railroad tycoon Leland Stanford, who needed to settle a bet. On June 15, 1878, in Palo Alto, California, Muybridge engineered some remarkable photos. He set up 12 cameras with newfangled electric shutters and modified emulsion on glass plate negatives. The champion trotter Abe Edgington was galloped by, tripping the cameras in sequence.

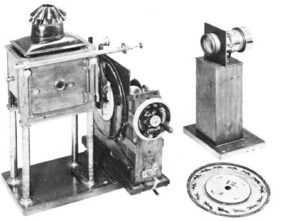

The photos, developed on the spot, established that there are times when a horse has all four hoofs off the ground. Something too difficult to ascertain by human vision alone. Eadweard Muybridge, (he changed his name and its spelling often) went on to invent the Zoopraxiscope. It was the first device that projected sequential stop-action photos onto a screen, creating the illusion of movement. He took his invention on the road. Thomas Eakins, who painted subjects in motion, helped arrange for Muygridge to work at the University of Pennsylvania. Muggeridge’s major accomplishments date from his three-year stay there, during which he improved his techniques. In 1887 Animal Locomotion, was published in 11 volumes. It contained over 100,000 photographs — elephants walking, women dancing and children climbing stairs — clarifying the mechanics of movement. Scientists and artists are forever grateful.

In a recent clickback, Tiit Raid of Fall Creek, Michigan pointed out the danger of letting your camera do the looking. This is certainly true for artists who rush their photos into paintings. But there are many situations where the camera can do a better job of not only looking, but keeping. Celestial photography and microscopy for instance. And then there are those who look through a telescope or a microscope and see art. Muybridge recognized and understood that the world is a more interesting and complex place than had hitherto been thought. The camera is an extension of the human eye. Through its retina, many an image can be deliciously stopped and considered.

Best regards,

Robert

PS: “The big artist keeps an eye on nature and steals her tools.” (Thomas Eakins)

Esoterica: Edward Muybridge (1830-1904) was born and died at Kingston-on-Thames, England. At one point, a newspaper reporter by the name of Harry Larkyns had a quick affair with his wife, perhaps even fathering a child. Muybridge tracked him down in Calistoga, California, and shot him dead. The court case that ensued dragged on, but Ed was acquitted — a justifiable homicide. I’ve asked Andrew to share some of Muggeridge’s remarkable photos, as well as my little contraption and some minutiae. See below.

Bob’s minutiaescope

The digital camera is set on close-up and remote shutter control. The remote trigger is at the top where’s it’s handy, and the infra red signal bounces off the white painted reflector near the front of the camera. The prongs at the bottom stabilize the device and give an idea of field of view.

Edward Muybridge (1830-1904) – Refresh screen to reanimate

Animations created by Charl Lucassen

Muybridge for reference

by Nancy Southard, Santa Barbara, CA, USA

As an equine artist, turned plein air painter, I used Muybridge for reference back in 1967. There is a stark reality and an innate excitement to his work. I have continued to paint the horse and the human figure in motion all these many years. My painting friend gave me this site recently and I enjoy it a lot. I’m always hungry for creative information, to get the juices going. It is wonderful to wake up to over a cup of morning coffee, purrrrrrrrrrrrr.

(RG note) Thanks, Nancy, and thanks for the purrr. And thanks to all who wrote to ask about books on Muybridge. Two excellent biographies, surprisingly both issued in 2003, are Time Stands Still by Phillip Prodger and also River of Shadows by Rebecca Solnit. A guide to Muybridge (current research) web pages, both available and de-listed, can be found online.

Necessary enrichment

by Gabriella Morrison, Maple Ridge, BC, Canada

We live in a world of marvels. Various optical tools, not previously available to people in recent past history, can be taken up and used to see aspects of the world from a variety of viewpoints. In the Bruce Mau exhibition last summer at the Vancouver Art Gallery, there was a room devoted exclusively to satellite imagery. From Muybridge’s camera to the very latest technologies, the information pool has grown by leaps and bounds. The visual artist community should obtain access to these technologies to better broaden their scope of awareness to the complexity of this world. These resources, on a continuum from simple to complex, are available to most artists today.

How incredibly enriching is this?

Same sites over time

by Ruth Phillips, Hameau des Cougieux, Bedoin, France

I love catching patterns through my camera lens. As a musician, it is like seeing the colourful fabric of an orchestral accompaniment. I grew up with the camera as a tool for seeing. When we were little, my father, the artist Tom Phillips, threw 20 darts into a map of the area round our house in south London and since then (about 30 years) he has photographed the very same 20 sites religiously on his birthday every year. Bollards come and go, a park is built and destroyed, the headlines change yet somehow stay the same and fashions come back… it’s beautiful.

The magic at our feet

by Rev. Sedgwick Heskett, Racine, WI, USA

I’m a writer, not a visual artist, and have admired how you use words to convey shadow, depth, texture, range, motion, field, foreground and background. This is the first time I’ve written, I think, and it’s because of your close-up camera. I seem to spend a lot of my time looking down: there are patterns on the world’s floor, and small objects that, seen individually, are indescribably beautiful.

(RG note) Thanks, Sedgwick. Aren’t you guys supposed to look up?

Simple means

Subject matter is all around us. In our cupboards, back yards, communities. It isn’t technology that makes it art… it is what we do with it… and / or without it. The eye (the greatest bit of technology known) is always with those of us lucky enough to be blessed with vision, and we don’t need trains, planes and automobiles to seek out subject matter. So, go ahead, invest in technology if it feels good, but give me a bit of water, a tube of indigo blue and paper and brush, and I’ll paint any subject in monochrome that you like.

Change of name and spelling

by Michaela Weiland, Seattle, WA, USA

I thoroughly enjoy your letters, and look forward to their arrival in my inbox. In this particular letter I noticed that Muybridge’s name was spelled in three different ways, including ‘Muygridge’ and ‘Muggeridge.’ I am curious to know whether this was simply a typo or did he use several spellings/nicknames? Never fear, there will always be an artist (or many) in the bunch with an eye for detail (or misspellings).

(RG note) Thanks, Michaela. As I noted in the letter, Muybridge changed his name and spelling throughout his life. Ed, Eadweard, Edward and Edwardo for starters. As for his last, all the above mentioned, including Muygridge are correct. No typo. I’ve met several artists who thought from time to time that a slight change of name would help to make them famous. I’ve often wondered if this was Edward James Muggeridge’s motivation.

Need for artistic cooperation

by Virginia Wieringa, Grand Rapids, MI, USA

It was delightful to see you and your Airedale, Emily Carr, out working with your minutiaescope. I didn’t know much about her namesake until I encountered her work through a little book I purchased in Windsor. I was thrilled by her work and her story. What a national treasure and a role model for women, or any artist who’s marching to their own drummer.

It seems to me that the minutiaescope and Emily Carr have some things to teach us in light of Todd Plough’s comments which seemed put a burr under Dave Wilson‘s saddle. She said: “There is a need to go deeper, to let myself go completely, to enter into the surroundings in the real fellowship of oneness, to lift above the outer shell, out into the depth and wideness where God is the recognized centre and everything is in time with everything, and the key-note is God.” (Emily Carr)

Carr, and fellow artist Lawren Harris were friends who disagreed on the topic of religion but respected each other’s artwork. Surely there’s room for us to all paint from our own perspective and use our own minutiaescopes; but like the blind men investigating the elephant, we can all come to our own conclusions without belittling the work of another.

(RG note) Thanks, Virginia. Actually that’s not Emily. That’s Dorothy. Emily Carr, the painter, is one of my heroines. Emily Carr, the dog, passed away almost two years ago. Dorothy the dog is named after Dorothy Gale, the heroine of the Wizard of Oz.

Privilege of the brush

by Veronica Stensby, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Bravo for your lucid and well-referenced defense of the camera’s “eye.” As an artist, my greatest challenge is to constantly switch gears from the fascinating realism and meticulous detail of photography to the personal vision of my own interpretation. Holding on to my initial response to an image, editing and cropping only the necessary information needed, then allowing a free-wheeling response that hopefully takes it a step further than the photo. Truly the camera widens our vision and love for the natural world around us. The challenge is to develop better skills in painting so I can offer a fresh look that doesn’t just copy the photo.

I can’t help but respond to Dave Wilson’s response to Todd Plough’s letter — advising artists to make a comment, or “get a violin.” Having been a working musician (classical piano) for over 30 years I must speak to the creative impulse that combines with intense training and that “isolation” we experience. Live performing is the ultimate “gift” of sharing the music and I stress that with all my students. It is of course ego-boosting and gratifying when done well but fraught with apprehension as well. One can still play in a closet for oneself and derive great satisfaction. My point being that music can be as challenging and creative an art form as any painting. Plough’s negative suggestion to “get a violin” really is comparing apples and oranges… we are all striving to be artists, skilled practitioners of our chosen fields and the growing never stops, we hope.

I visited the exhibit Rembrandt’s Late Religious Portraits at The Getty Center recently. Aside from the intensely personal connection with his subjects Rembrandt was able to convey in his paintings, the brushstrokes were revelatory, and well-noted in the accompanying brochure. Rough application and blazing bits of color in the foreground, with extraordinary touches of gold-like threads and swaths of beautiful creamy whites in the fabric. Also the symbolic painting of St. Bartholomew’s hands (with loose skin) as he would later be “skinned alive” in his martyrdom.

To bring this all together I mention a book from the “Rembrandt Research Project” called Rembrandt: The Painter at Work, wherein Van de Wetering offers his personal observation: “If we want to get an idea of the discipline and skill of a painter like Rembrandt today, we would do better not to look at the great majority of our contemporary painters, but at the performing musician or ballet dancer. In these arts, it is still understood that professional skill can only be built up through endless practice from an early age on… the same pertained just as much in Rembrandt’s day to the art of drawing and painting. But it should be added that whoever inquires more than superficially into the careers of those dancers and musicians of our own time who have practiced all their lives, will realize that only a few are able to command that unique set of qualities that are necessary in order to develop into major artists. Without that basis of skills, there is, however, no way that this can happen.”

What a privilege it is to be able to take brush in hand and put paint on paper in this troubled world. Some of us take a stand for beauty and soften the pain of the world. Others must point out the fear and anguish of the soul through their art. Let us all share our vision, but remember to practice our craft to better express that vision.

Ego, or the sublime?

by Sally Pollard, Weiser, Idaho, USA

I have found that being too original loses the audience. Maybe I have not had the patience to find the right audience and have instead stepped back a bit to re-examine originality and creativity. One thing I have observed is that people want to relate to a work. Things too original don’t obviously show where the ideas came from. Either you have to educate them about what you are doing to show them the lineage of your thinking or have the power of a curator or institution do it for the audience. Another way might be to do multiple readings, using a Trojan horse of a familiar image wherein you can imbed your creative tidbits. Can you build a better mountain head or sunset or basket of peaches?

I have turned back to being less original in subject matter and trying to look deeper at what is familiar and try less to be a god creator myself.

I am currently reading Peter London’s, Drawing Closer to Nature. In it he describes his uneasy feelings about an incestuous creative lineage of mainstream art, art making reference to other art. He then goes on to describe an epiphany he had at the beach one cold and blustery day, which drew him back to communicating directly with nature. And I respect that. On the other hand I wonder if another plein air painting is like meatloaf, familiar and individual, maybe better the next day or merely leftovers?

Creativity implies a god-like quality. I’m also wondering about the spiritual nature of art. Can you better the world through art, inspire people to become one with god or nature? Is it just something that comes through your work automatically if you are inclined that way anyway? I always thought if you had a message to send, then send it snail mail or email, don’t make it into a work of art. But art, like handwriting, reveals things unintended. I have more questions than answers. Can art be spiritual or is that just another visual illusion? Art the creator, god the creator. Ego, or the sublime?

Artist’s reflection

by Eve Schell Okumura, HI, USA

I have noticed that in photographic portraits, the artist’s feelings about the subject shine through. Faces have, and will always fascinate me. I have come to believe that the retina is an extension, not only of the artist’s eye, but also of their spirit. It is interesting that when taking photos, often the beauty and prejudices of the photographer show more in the photo than the subject itself.

Barter

by Sara Genn, Paris, France

A poem by: Sara Teasdale, contributed by Sara Genn

All beautiful and splendid things,

Blue waves whitened on a cliff,

Soaring fire that sways and sings,

And children’s faces looking up

Holding wonder like a cup.

Music like a curve of gold,

Scent of pine trees in the rain,

Eyes that love you, arms that hold,

And for your spirit’s still delight,

Holy thoughts that star the night.

Buy it and never count the cost;

For one white singing hour of peace

Count many a year of strife well lost,

And for a breath of ecstasy

Give all you have been, or could be.

Oranges oil painting |

You may be interested to know that artists from every state in the USA, every province in Canada, and at least 105 countries worldwide have visited these pages since January 1, 2005.

That includes Norma Laming, UK, who wrote, “The mantra you refer to is “I hear, I forget… I see, I remember… I do, I understand.”