Dear Artist,

At the National Army Museum in Chelsea you can get an understanding of the lives of men and women who have served in the British army. It’s hands-on from the Battle of Agincourt in France to today’s action in Iraq. I found out how heavy a cannonball is, tried on helmets, ducked through a WW1 trench, looked down the sights of a Lewis machine gun and shot up some tanks in computer-generated modern warfare. What art this hardware is. What creative talent has gone to war.

A special exhibit takes you through the folly of the Crimean War of 1854-56. The British Army was pumped with pride, arrogance and ignorance. The British public was led to believe it would be over quickly and a piece of cake. Incompetence in command brought on disasters like the “Charge of the Light Brigade,” where 600 soldiers rode into murderous Russian fire in the “valley of death.” In the trenches besieging Sevastopol, soldiers in summer uniforms struggled to keep warm in the Russian winter. They were without sufficient food and there was little or no cooking fuel. Army hospitals lacked supplies and thousands died from cholera and dysentery. By modern magic in this museum, Florence Nightingale talked to me about the sick and legless men among her helpless nurses.

The Crimean War was handsomely painted. The museum has giant panoramas of encampments and battlefields, decorated generals in full swagger, horse and infantry charges in full roar with surprised hussars grimacing. Even the battles they lost are optimistically illustrated — a soldier or two face down in the muck for good measure. Much of the art was commissioned after the fact. Some of it was illustrated in Punch and other popular journals. This war was the first foreign adventure with war correspondents and daily information for home consumption. There are some of the earliest war photos of Roger Fenton.

I’m writing to you while sitting in some sort of missile launcher. As I press these laptop keys and view this screen I’m aware of another keyboard and screen nearby. I’m thinking that there’s no limit to imagination in the design and romance of human tragedy. Also, how artful — we do not now need to meet the ones we kill.

Best regards,

Robert

PS: “The Russians, in one grand line, charged toward that thin red streak tipped with a line of steel. The 93rd never altered their formation to receive that tide of horsemen. ‘No, said Sir Colin Campbell, ‘I did not think it worthwhile to form them more than two deep.’ ” (William H Russell, The London Times, October, 1854)

Esoterica: Hanging up in the modern warfare section there’s a beautiful, tiny reconnaissance aircraft called the Phoenix. It’s flown from a ground-based, portable computer by a person who needs no flying experience. Its purpose is to send back real-time images of enemy movements or installations. Like a video game it paints a simplified picture of a distant target and informs ground forces when and where to fire. When finished its job, the plane pops a parachute and soft-lands nearby, ready to fly and paint again.

Crimean War Art

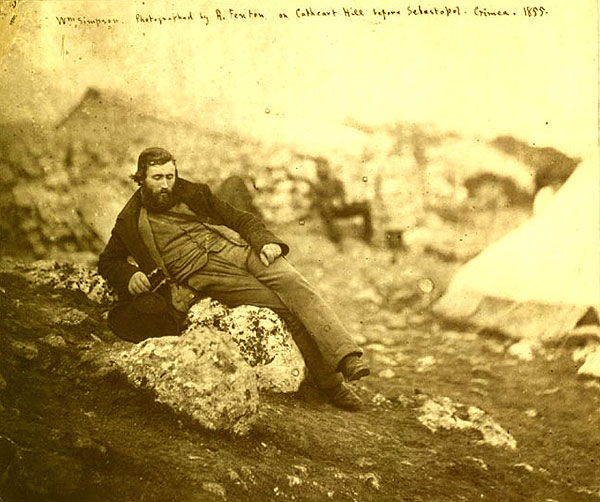

William Simpson in the Crimea

Photographer: Roger Fenton

“Last Review Before the Charge”

(British Lancers, Crimean War 1854)

art print by Mark Churms

“The valley of the shadow of death”

Photographer: Roger Fenton

“The thin red line”

painting by Robert Gibb

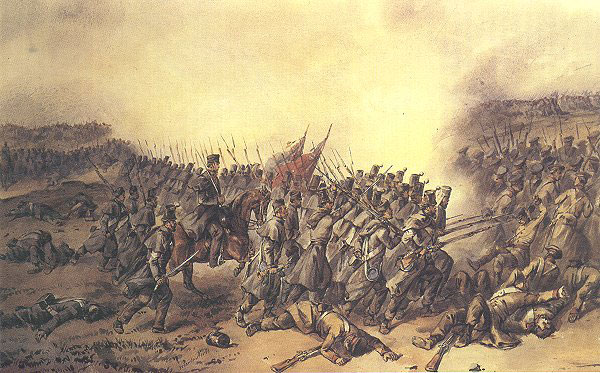

“The Charge of the 21st Royal North British Fusiliers at Inkerman, Nov. 5th, 1854”

painting by Orlando Norrie

“The Charge of the Light Brigade at Balaklava”

painting by William Simpson

notes: the 93rd Highlanders, commanded by Sir Colin Campbell, awaiting the onslaught of the Russian cavalry in line without a movement in their ranks or an attempt to throw themselves into square.

notes: about 8.30 am when the Regiment charged and repulsed an attack launched by two Russian battalions. Lt.-Col. Ainslie, later mortally wounded, is on horseback.

notes: view is from the Fedokine hills across the Causeway toward Balaklava harbor.

War not artful

by Li Hertzi, Carlsbad, CA, USA

I spent much of my childhood playing around cannonballs at Gettysburg, hearing the stories of immigrants’ real life experiences of war, the romance that they were sold and the horror of the reality of it — It is not artful.

Our work defends hope

by Todd Plough, NY, USA

Unfortunately the price of freedom is always blood. These opinions fly through the air by the grace of those who defended the freedom of their countrymen to the end. What an ironic thing, those who bought it dearly seldom get to own it yet it is they who understand how precious life is. The ultimate point counterpoint. As artists our job is to keep the faith and help humankind to remember beauty and thus the promise of happiness. Our work defends hope, the most precious homeland for any soul.

Correction on climate

by Oleg Korolev, Crimea

Thank you for the letter. I appreciate your writings, though the words “Russian winter” surprised me, because actually Crimea is situated much farther south than Great Britain. Sevastopol belongs to a sub-tropical climate area. There can be cold in the wintertime, but not colder than in France for example.

War movies lack the smell

by Sarah Schultz, MD, USA

During the 1980s there was a book and TV series called War. It also showed us the beautification of war. Then explained what it was really like… the most lacking sense when viewing war movies is the sense of smell.. that of death and the dying. The last part explained how in the future we can kill without ever seeing the enemy. The movie Toys also showed how children could be warriors at their computers, shooting real guns, tanks, etc. The destruction of war is not beautiful… Life is precious. The artists who portrayed war were doing a job. In many instances they were told what to paint.

Wars part of family history

by Alex Strachan

My father won the MC at Vimy Ridge as a Scottish Infantry officer, he fought through the battle of the Somme and got a bullet in the brain after Vimy and somehow survived. Nearly all his friends were killed in the war. Twenty years later my brother jumped off a landing craft in Normandy and got very badly wounded. My uncle survived several crash landings in his Spitfire to fight the Battle of Britain, Battle of Malta and then Northern Europe. My mother was part of a commando group — morse operator, decoder and encoder based in Scotland — that fought the Nazis in Norway and was at war crime trials in Oslo at the end of the war. My grandfather flew early aircraft out of catapults from naval vessels in the First World War and commanded a Fleet Air Arm base in the Second World War. My mother’s cousin was killed commanding the Canadian troops in Hong Kong, my grandparents house was obliterated by a German bomb and my father lost most of the use of one of his eyes from a V bomb that landed in London in the Second World War. War played a large part in my recent family history and if you go back a generation beyond my father — he was born in 1896 — it had played a large part in many of my more distant relations’ lives as well.

How Shakespeare, Homer, and all the great bards must be laughing or crying looking at how little we have progressed in 500 years or 5000 years in the understanding of human character. But then unfortunately the average “developed world’s” citizen is not being encouraged to study history or literature, and with that lack of knowledge goes the capacity to understand what we are capable of and what we are not. Samuel Beckett said, “Try again. Fail again. Try better.” A brilliant woman introduced me to Beckett’s words and it seems to me they sum ourselves up for what we are. They strip away and at the same time illuminate the arrogance and ignorance of our human condition.

Excellent military art

by Julie Rodriguez Jones, Sparks, NV, USA

The finest military art that I have ever seen was exhibited at the Reno Air Races which is held at Stead Air Field in September of every year. It was not only excellent art but also very poignant and did not all necessarily glorify war. It told about the lives of the men and women affected by the war. The history was palpable. There were images of bomber crews before takeoff, men reading letters from home and paintings of actual combat. Most of the art was from World War II but there were also images of astronauts, spacecraft, and aviation figures such as Amelia Earhart. Many of the images included autographs of the men or entire crews shown in the art.

I had access to the “pits” where a variety of aircraft were being serviced and prepared for the races. It was a unique opportunity to see aircraft close up and inspired some art after the show. Before we left I went back to the art several times. I plan on attending again in 2005.

Stupidity of war

by Ernst Lurker, East Hampton, NY, USA

There is a beautiful male Cardinal in our garden that tries persistently to fly into our windows. At times, he bangs against the panes about 10 times per minute. We’ve tried everything, hung sheets up, taped paper against the windows, bought decals — nothing helps. This has been going on for over two weeks. You wonder about the bird’s instincts and about his inability to learn. For a moment I compared his intelligence to human intelligence; I felt rather smug and felt sorry for life that’s not as evolved as we are. But I changed my mind quickly. The enormous stupidity of war came to mind. A higher intelligence would feel sorry for these warring idiots the same way I felt sorry for the bird.

Then we even bring God into the picture with phrases like “God bless America.” It’s obvious — God doesn’t help the bird, but neither does she help the warriors. It just makes our stupidity so much worse. We are on our own. The only hope is that we are now capable of changing our mind and our behavior. The bad news is, it won’t happen in our lifetime.

Peace is the way

by Susan Burns, Douglasville, Georgia, USA

I can’t help but wonder what great art we will be doing with all that energy used to make weapons when we finally realize that war is not really in anyone’s heart. (There are concepts in our heads, but we all want to be loved.) Yes, the violence we invest a lot of effort and money into is enmeshed into our society through fear of humanity, creating economy, proof of ego etc. For several years, I worked as a mechanical draftsman on top secret military weapons and most of my coworkers were military men that had fought in WWII. These guys had great, daring and sad stories to tell sometimes, but were very quiet for the most part. Aged before their time, I know now that I didn’t appreciate their experience, as I was so young at the time. Lives forever changed by what they saw and experienced, were often lives of deep dark pain and suffering. I would have to say that they themselves were in shock at the things they so naturally did in the name of fighting, winning and protecting. I hope boundaries become smaller and smaller until we realize that we are more the same than different. Think peace. “There is no way to peace. Peace is the way.” (Gandhi)

Soft bombs offensive?

by Bee Hylinski, Berkley, CA, USA

I read with interest your piece on the art of war. However, it triggered a completely different issue for me. I have a friend and fellow fiber artist who has some work in an exhibit by Fiber Dimensions, a group of fiber artists, which is currently at the San Francisco Bay Model. Her work is a series of knitted bombs, I guess as her way of saying that the only bombs we should be making are soft ones that won’t hurt anyone. The Army Corps of Engineers which owns and runs the facility wants them removed from the exhibit. Why? I am not sure, but they are reacting to them really negatively. Maybe they build things and don’t want a symbol of destruction in their building? Maybe people are complaining because bombs are pro-war (this is Marin County after all), but they are of soft fuzzy wool. I think they can be interpreted many different ways.

My question is how much does the First Amendment protect legitimate artistic expression (I draw the line at the cross-in-the-toilet type of expression, personally, and not on religious grounds)? Who has the right to cry foul when an artist makes a statement, especially one that can be taken several ways? If it is done purely for the shock value, I don’t have much problem with jurying it out or removing it from an exhibition. But when it is good art and really expressive, can you remove it because someone might take it in a way that is offensive to them, but not to others? I don’t know.

I am a fiber artist and a retired lawyer and I think that the Supreme Court has taken the scope of the First Amendment way out of the realm that the Founders intended. It now trumps all other rights, rather than being balanced against other constitutional rights, as it should be. So I find it really amusing that I am arguing on the side of applying the First Amendment in this one. I don’t like censorship, but I do think that there are times when it is appropriate, and these bombs are not one of them. What do you think?

Unscrupulous artists

by Pat Weekley, Clovis, NM, USA

In response to the letter by Hans Werner, I think he has a valid point and it seems to me more of a problem as technology improves. One could display a ‘painting’ and as soon as it sold, replace it with another identical reproduction. I know a reputable art dealer would not do this but what would stop an unscrupulous artist from going to another locality and selling another reproduction? I know that it is hard to resist this kind of thing but I have talked to some artists who are needing to sell in order to live and I recognize the temptation. How can a buyer tell what is real and what is not?

“Art maniac” in pain to see Masterworks

by Lyn Cherry, Maryville, TN, USA

Bernard Victor’s letter mentioned, “Monet, Whistler, Turner at Tate Britain,” as one of the many exhibitions in London at this time. It brought to mind an incident which occurred last year, and I thought other “art maniacs” would enjoy it.

An artist friend and I were in Toronto, Canada last July. We were there to meet some artists we had become acquainted with through the online artists’ community, WetCanvas.com and to visit some art galleries. We had tickets for the Monet, Whistler, Turner exhibition for the morning after our arrival. Alas, I had a quite severe fall in the hotel bathroom, resulting in a very sore ankle. I usually use a cane, but had planned to use an electric mobility vehicle while touring Toronto. It was not there when we checked in, so the hotel loaned me a wheelchair to use until it arrived. I was not going to miss our scheduled time to view the exhibit, and refused to go to a hospital emergency room. So we called a limo, loaded the wheelchair and me and set off for the exhibit. It was wonderful! Even viewed through a veil of steadily increasing pain!

We carried on with our delightful visit, meeting the WetCanvas! artists and doing some sightseeing. Upon returning home to Tennessee, I hobbled around for a while in quite a bit of pain and then finally went to the doctor — I had broken my ankle in the fall!

The moral of my story is that even a broken ankle won’t stop an artist from viewing the works of the masters, and enjoying it mightily!

Composition 26 oil painting |

You may be interested to know that artists from every state in the USA, every province in Canada, and at least 105 countries worldwide have visited these pages since January 1, 2005.

That includes Denise Bezanson who wrote, “My great grandfather served (and survived) the Crimean War, with the Scottish Highlanders, and I have his sword from the War in my living room, in a place of honour. Your letter touched a personal note.”

And also Laura Wilhelm who wrote, “When we make art we do meet the ones we kill. We face our own humanness if we can approach a canvas or a sculpture honestly and openly. We meet ourselves.”