Dear Artist,

This morning, Matt Krumenauer, a student of Fine Arts and Theatre at the University of Wisconsin, asked: “Do you have any suggestions on how to determine a starting selling price? Especially for a younger artist with no reputation. I’ve entered works into various showings and contests — and have been asked to sell. What to do?”

Thanks, Matt. My advice to young artists of all ages is to start off cheap. My rationale is that your prices can always go up but should not come down. Early low prices ensure that people will take an early position in your career. Nothing better than a penny stock that goes through the roof. At your stage, it’s easy to feel that the investment in your education entitles you to higher prices right out of the gate — especially when you see the substantial prices of instructors and others. Not so. Minor “green feedback” is better than finding yourself dead in the water.

After a few sales at the bargain-basement level, you can then look to price management in a more professional manner. In my view, prices should rise sensibly and regularly. Ten percent and once a year is the reliable norm. With gallery representation there has to be a reasonable base so their percentage will make it worthwhile for them. Consultation with galleries is useful. Comparative price-checking is useful but not always germane to your uniqueness. There is no single axiom that determines at what price paintings or other works of art should be. Generally speaking, size, not the amount of detail or time taken, is the better guide. Thus an artist can provide a range of prices that have various price points. At the low end there’s an opportunity for entry-level collectors, while at the high end you can see if the big spenders will go for your work. As a guide you might take a look at the pricelist on my website. Don’t forget that I’ve been in the business for a few years and have stuck pretty closely to the 10% rule.

The joy of your art process is one thing. The commoditization of your art is another. It’s something we learn to live with if we wish to stay in the game and have a life. My advice is to start low and yet keep an eye on the big picture. There are rewards for those who do.

Best regards,

Robert

PS: “Artists should separate pride from price.” (Eleanor Blair)

Esoterica: There’s something to be said for making up your mind on a pricing plan that will last a lifetime, setting it in motion, and forgetting about it. With compounding you’ll get there anyway — much to the satisfaction of your early collectors. When work is half decent, there’s justice. The main thing is to catch the breeze and sail on. “There is too much talk and gossip; pictures are apparently made, like stock-market prices, by competition of people eager for profits. All this traffic sharpens our intelligence and falsifies our judgment.” (Edgar Degas)

Changed market

by H. Margret, Santa Fe, NM, USA

Your 10% rule is attractive — and I know you’ve been at this 25 years. But what about a market that has changed? I’ve been in Santa Fe for 12 years, sold art on Canyon Road for 7, raised up a good group of collectors on unframed paper originals, starting at $40 each… then, our tourism slowed. Last year, I made about $5,000, when $30,000 used to be the low average. Artists here don’t talk money, but I have watched dozens of bankruptcy cases, including Bev Doolittle. I listened to artists pontificate on raising prices, then file for bankruptcy. Art is like other markets, when prices drop in antiques, don’t they drop for art? What of the artist who is not selling at the continually raised prices?

(RG note) Thanks, Margret. One of my axioms is that you should not become too dependent on any single geographic area — particularly tourist destinations. Like the gold rush days, lots of miners rush in. Bonanzas for a while — galleries and artists proliferate — and prices advance too fast and everyone gets drunk in the bars. This is what happened in Santa Fe, Taos, and to some degree Scottsdale — and it may be coming to a town near you. Distribute widely, stick to ten percent or thereabouts, and don’t believe everything you hear. Artists need to take control during their own lifetimes so their stuff doesn’t get thrown around like Royal Doulton.

Started out expensive

by Brian Petroski, Schuylerville, NY, USA

So, I agree with what you say about starting off cheap with your artwork, however, what do you do if you’ve started off on the expensive side with little sales? I began pricing my work about 6 years ago when I started painting enough to sell, however, I let my pride price my artwork instead of seeing the big picture and now I’m stuck in a jam. Everyone loves my art, but all complain that it is too much for them. If I lower my prices it automatically devalues the work in the eyes of all who know my work and would really annoy clients who have already purchased. I have been slowly trying to show my work in markets where wealthier clients hang out. Do you think this is the right strategy, or should I lower my prices? I’m trying to dig myself out.

(RG note) Thanks, Brian. Adding exposure in more upscale environments is the prudent move for you for now. Give yourself a couple of years to test in different areas. Make sure there’s a big enough cut in there to motivate your new dealers. If this strategy doesn’t bring you to ‘catch up’ I’ll eat my Bentley.

Removing the emotional attachment

by Jean-Pierre Beeks, Montreal, QC, Canada

I have found the major flaw in most artists is in fact being too proud of their work, and trying to exact a price that reflects that pride. I personally had a bigger problem and that was being too emotionally attached to my work at first (which I suppose is the worst kind of pride). I would go so far as to judge the person offering to buy one of my paintings as someone would an adoptive parent! That effectively rendered my paintings priceless.

In the end those “children” I couldn’t put a price on just kept hanging around and following me from place to place. I learned that they needed to get out there on their own and that I needed to evolve as an artist. I needed to remember that my best work is the painting that I have yet to paint. The way I started was to simply take what it cost me to make a painting: paint, canvas, brushes etc. excluding rent and my time and double or triple it. I sold a lot of paintings and a lot of people were very happy, especially me. I could start looking forward without something from the past staring back at me!

When to raise prices

by Jeanie Jones, Lubbock, TX, USA

Great letter, Robert! Your articles are very informative and I enjoy them very much. I like your idea of pricing. But, I need to ask a question. I started out low as you recommended. Do you think it is time for me to go up on my prices? I will be 73 in September.

(RG note) Thanks, Jeanie. If you’re feeling well, now’s the time to raise them a little bit. If you’re feeling poorly, raise them a lot.

Pricing guide

by Joy Hanser, Vancouver, BC, Canada

I suppose the easiest way to price paintings would be simply to set a price by-the-square-inch, however that renders small gems very cheap and larger works quite expensive. Is there some easy way for a relatively unknown-in-the-fine-art-field artist to a) evaluate a starting rate and b) do a simple pro-rate to keep prices in line and adhere, as you suggest, to a no-brainer pricing guide and be done with it?

(RG note) Thanks, Joy. And thanks to everyone who wrote with this idea. Joy has put her finger on the problem with the square-inch formula. A sliding scale is more appropriate. One which has a work or two in each price zone. Don’t forget that many people decide beforehand how much they are going to spend. As they say in the selling game, “the salesman’s job is to find out how much they’ve got, and not take a penny less.” See letter below.

Refining the square-inch system

by Matt Welch, Decatur, AL, USA

My solution has been to base the price on square inches. My approach is to take my most frequent sold size (say a 16 x 20) and translate the price into a value per square inch. This usually occurs when entering a new market and is established early in the process (To determine the initial pricing usually takes a little research and a few visits to galleries and shows). Some adjustments are needed for smaller pieces to establish a minimum pricing threshold that prevents these smaller pieces from being too attractive to collectors. I have found that pieces having surface areas less than 200 square inches need a higher per square inch value than larger works. When I have established the price, I then take into consideration my out of pocket expenses, which vary according to size and finished product (i.e. framed, unframed, special materials, etc). So far, this approach has worked and has resulted in fairly consistent sales. I have also found that markets with higher thresholds require adjustments, much the same way other commodities carry higher values within these markets. This approach is simple to use once that initial value is established, and the application easily translates to all size works.

Ballpark figure needed

by Lucy Bates, Fruitvale, BC, Canada

I appreciate your comments on pricing. You have given your price list that is on the high end but you have not given actual figures as to what “low pricing” or what “cheap” is. Some of us need to have it spelled out. If we are pricing by size (per square inch), what is a good starting price or is that too individual to determine? Nevertheless, could you please give a ballpark figure?

(RG note) Thanks, Lucy. This is difficult to answer because entry level pricing is different in different geographic areas. Obviously entry level is different in Moscow and Havana than it is in Chicago or Fruitvale. It’s got a bit to do with how much people are already spending in your area for your sort of thing. Think of your early pricing as a test. Look around at the competition, beat the competition in price, and make your stuff better than the competition.

Hang on to early gems

by Norman Ridenour, Prague, Czech Republic

Sometimes one does a really good piece early on, you know it. Don’t give it away. You may have to hold it for a few years but you will get your price. I had a piece in this category. It was a bit different from my normal work. It had an inner tension and dynamic to it. I carried it around for several years, raising and lowering the price. It was an awkward piece to get in and out of the car. Finally I tripled the price and put it on show. It sold that day and when I delivered it, it bumped a George Rickey piece out of the living room.

Picasso’s dealer advised him to just hold his good work in storage until he had a reputation. It’s hard to imagine today, Picasso as a struggling artist, but he was.

Pricing of limited editions

by Helen Scanlon, Hampton, CT, USA

I am just starting out and your letter gave me a better idea what I had to charge for my originals. Do you have any suggestions on pricing limited edition signed and numbered prints?

(RG note) Thanks, Helen. Most areas these days are in a down-cycle for limited editions. The heady days of bamboozling prices are largely over for the time being. Thanks mostly to the giclee process, there’s lots of product out there. Having said that, you have to be careful as inexpensive prints will actually steal from the sales of your more expensive originals. For the time being keep your editions low, don’t print full editions out of the gate, and give serious consideration to offering them in different venues than your originals.

Working with a handicap

by Jim Webb, West Chester, PA, USA

It’s not uncommon for us artists to bemoan the ups and downs in the art field andat times feel depressed. For those who suffer a bad case of HSP, try this one on for size. I invite you all to visit the website of Eric Mohn. I’m a handicapped artist that has exhibited with Eric in several shows. My handicap simply pales when compared with other artists who have triumphed over their limitations. Eric paints watercolors with the brush held in his teeth. It takes him two weeks to complete a work. I’ve met Eric several times at the various shows and what a happy, generous person he is. I know of a few painters who have been declared legally blind and the work they produce is amazing. More should be known about handicapped artists and what they have accomplished.

Handy method for determining price

by Arthur Nelander, Kaneohe, HI, USA

In George Washington’s days, there were no cameras. One’s image was either sculpted or painted. Some paintings of George Washington showed him standing behind a desk with one arm behind his back, while others showed both legs and both arms. Prices charged by painters were not based on how many people were to be painted, but by how many limbs were to be painted. Arms and legs are “limbs” therefore painting them would cost the buyer more. Hence the expression “Okay, but it’ll cost you an arm and a leg.”

Three degrees of appreciation

by Norman Ford, Waynesboro, PA, USA

Being self taught it has taken a lot of work and study to evolve. A few weeks ago I entered four of my oil landscapes in a county art show and two of them earned honorable mention! More recently I entered four different oils in another show and took both First Place and Third Place! Needless to say the ribbons helped my self image but they didn’t put food on the table. I decided to find a spot along the road and set up a “one man show”. Before the wind flattened my rack I had sold five paintings each reasonably priced! But what excited me most was hearing the “oohs” and “aahs” from those who stopped and looked at my work.

Pricing sculpture

by Laurie Smith

I’ve been sculpting 25 years but just invested in bronzes and am in three shows this summer: Marin Art Festival, Laguna Beach Art-A-Fair, and Loveland. I want to start low but I also can’t afford to lose too much money selling a piece. There are certainly more costs than mold and pour, and I’ve tried to include them. I’ve done a spreadsheet of costs in three sections:

— Tools of the trade, which last for years: I spread over 100 pieces. (No it didn’t include college or classes)

— Promotion: application fees, camera, photos, Slides, bio, cards, pedestals, light bar, umbrella, etc. over 30 pieces

— Presentation costs: booth fee, hotel, trailer rental, lighting over 10 pieces; then add mold (divided by four) and pour/patina/base) to my price.

I came up with a base pro-rated cost of $870 per piece before the foundry. This doesn’t include my time or talent. When I do my own pour I have cost of bronze or mold products so I add some for my effort. I’ve heard divide by three. One third for the foundry, one for artist, one for gallery. Then I’ve heard triple the foundry price. I’ve also heard you don’t undercut the gallery price but also discovered that the high costs I’ve paid to get into and show my work really equals the costs a gallery incurs and mine are increasing.

Long winded but you now have my current solution as I come out for my first shows. It amazed me to see the actual costs of preparing bronzes for the market. It also helped me justify a price just to cover costs and later to make a profit. With my method, I won’t get my costs back until I sell 100 pieces and with each show, my costs escalate. I’ve also learned to have one or two inexpensive items that you sell at a loss just to help pay the bills.

What do you suggest? Also, how do you determine an “Artist Proof” for bronze, and how many can you have? Does the artist do the work on those? What happens when the artist makes or works directly on all pieces?

(RG note) Thanks, Laurie. One of the most effective ploys for sculptors is the large piece in a public place or private architectural setting. With the percentages being set aside for art associated with buildings these days, this can be a pricy piece, rather than a lost leader. Try up-scaling. With regard to artist’s proofs in bronze, 10% is still the norm. In most cases they are identical in craft and personnel involved. A specific “remarque” (a special touch, side drawing or uniquely incised area) is a nice bonus for the buyer but it need not necessarily be charged for. Sculptors should touch all pieces with the exception of when they happen to be dead. Sculpture has a unique “born again” feature with infinite reproductive immortality.

Formulas for pricing art

by Dar Hosta, Flemington, NJ, USA

I was so glad to see the topic of pricing in today’s letter. I think when we artists figure this out, we are halfway “there.” I have been selling my art in a professional manner for over 8 years now and definitely started (and stayed) at the bargain basement level until a number of things began to happen. First, and most importantly, people continued to buy my work and, notably, the people who purchased my work often had a common demographic and became some of my earliest collectors. Second, my confidence grew as time went on and I felt a new sense of pride in my work, seeing it as a real opportunity for a career that would earn me an actual income. Third, this pride and confidence led me to create a professional work environment for my art: a permanent studio with good tools and places to put them, high quality art and framing materials that I could tell my customers about, professional promotional materials that could be given to prospective clients, and things like a professional software program to organize my mailing list. I might also add that I work with very few galleries, opting to do mostly juried fairs and festivals, or appointments with private clients in my studio, and have invested in quality, professional displays for my work, presenting myself at these shows in a way that is professional, organized and confident. I once read an article by an artist who claimed that we, ourselves, should always look as though our art creates income for us and that the sloppy, eccentric artist look should be reserved for our studio hours rather than our public appearances. In this age of impression management, I agree with this wholeheartedly. Black pants and shirts are easy, folks. When facing the public, keep your ripped, painted blue jeans and messy t-shirts at home! Despite all these things, pricing can still be tricky for me, both for my originals and my reproductions. So, a couple years ago, I finally decided that I needed an actual formula for calculating the price of my originals. I took the highest priced original I’d sold in the last six months, along with one that was more moderately priced. I figured out the price per square inch and then averaged these two pieces. Then, because I also freelance as a designer, I considered how much I wanted to make per hour and I figured this into my per inch price. (My art work tends to be very time consuming and I often have pieces that take many hours to complete). Finally, I must include the cost of framing and the time it takes me to complete this task since I do this by myself also, paying myself here my hourly “labor” rate rather than my hourly “creative” rate. This all eventually became second nature to me and I find that I don’t really need to do all the figuring anymore and can make adjustments for market value and material cost increases as needed without thinking too much about it. There is one other factor in pricing art that is best illustrated by the following anecdote: Last year I created two originals that were basically the same in materials, time spent and size. They were meant to be sold as a pair, though eventually sold separately to two different people. One day, a man came out and asked me what I know many people had been thinking, “why does that one cost more than the other one?” I replied, simply, “because I like it more.”

As a professional artist, there isn’t always a regular paycheck. It can be tempting to sell off something cheap when the bills need to be paid and you haven’t sold a piece in a while. I avoid this practice, however, because I feel it compromises the integrity of both my work and myself. I will sometimes work with collectors and regular customers, but as a general rule I do not “discount,” particularly when this is the first question that a customer asks me. I find it troubling when I see a fellow artist letting someone haggle them down, down, down. I encourage the artists I know to never, ever downgrade their work in front of a customer, in price or in quality of execution and/or design, and to only speak of their art and their life as an artist with pride, confidence and professionalism. It is said that we have the ability to teach others how to treat us. We must, I feel, teach our clients that our work is worth every penny and that it will give them satisfaction for many years to come.

Workshop promotion

by Sheila Parsons, Conway, AR, USA

I have been asked to teach a class in the Yukon as a new location for watercolor (and other media) workshops. I have been teaching workshops extensively for 20 years now and am well known in my area and across the USA. I have only ever done one workshop in Canada and that was on Vancouver Island. I have no mailing list for potential students of watercolor plein air workshops in Canada. Can you direct me to an agency or someone who could provide me with a listing of local arts organizations and specifically watercolor groups?

(RG note) Thanks, Sheila. Our mailing list would help fill your workshop fifty times over. But of course we do not give out our list. I suggest that you put a link to your workshop on our Workshop Calendar page. More than 5000 artists, collectors and other interested persons cruise through these listings every day.

Science gets a bad name

by Vickie Turner, Nanoose Bay, BC, Canada

That letter by Ted Berkeley in the last clickback got me so steamed I had to leave the room to cool off! What arrogance! What ignorance! I’m a physicist (as well as an artist — and extremely HSP) with a special interest in quantum theory. If it all merely comes down to quantum particles (or wavelengths), we’re no different than inorganic matter. It’s the arrangement, the organization, the inter-relationships, the communication, the expression of even the smallest “matter” that determines outcome — i.e., the “spark” that distinguishes life (and that doesn’t even begin to distinguish intelligent life). This guy is one reason why science gets a bad name.

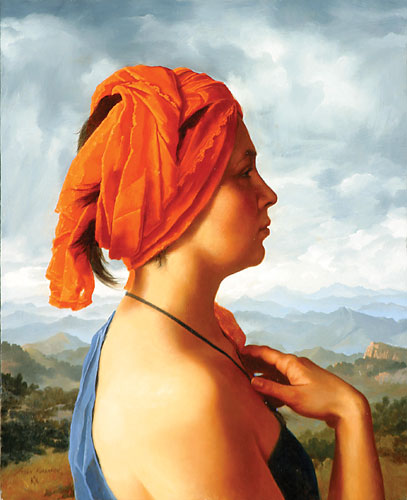

Orange Turban oil painting |

You may be interested to know that artists from every state in the USA, every province in Canada, and at least 105 countries worldwide have visited these pages since January 1, 2005.

That includes Atiya Nadeem of Muscat, Oman who wrote, “I had my first solo exhibition this past January. You can’t imagine how wonderful it is to join in this conversation you cause to happen twice a week! It more than makes up for the lack of such a coming together of artists, where I’m living right now.”