Dear Artist,

If you ever feel guilty about using a projector, consider this — you’re in great company. Johannes Vermeer (1632-1675) was born and lived in Delft, Holland. A picture dealer, he was never able to support himself from his own art. Perhaps he had a patron at one time, but it’s known that he lived in the home of his wife’s mother and raised a house full of kids at a time of war, debt and not much interest in art. No one knows for sure what he looked like. There are perhaps 35 known paintings by Vermeer, most of them small. Today we see them as pearls of poetic serenity.

Many curious folks have taken a run at the origin of Vermeer’s work, most notably Philip Steadman in his book, Vermeer’s Camera. Brilliant perspective, compositional structure, checkerboard tiles, paintings by known artists that appear in his interiors, accurate wall maps of the time, well understood light and muted colours — with Vermeer there’s lots to talk about. And there’s controversy.

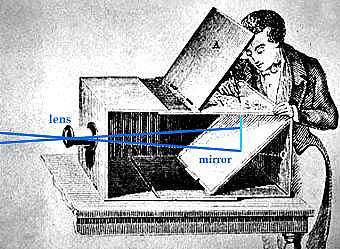

Vermeer’s working places — two separate rooms — were probably renovated to become camera obscuras. A lens and a curtained cubicle provided a projected image of an interior on the side wall — upside-down and backwards. For many paintings Vermeer traced images of models and particular furnishings that were set and posed close to distinct windows and light. Later he transferred these drawings to his canvas. A few paintings may have been projected and painted directly. Artists, particularly those with projecting experience, looking closely at the work can spot the problems inherent in projected transfer. They see second-generation line victimization, inability of the artist to tell what’s going on in the shadows and dark spots, and camera-characteristic mannerisms not compatible with standard creative thought and analysis.

One of the convincing arguments for the use of a lens lies with Vermeer’s best friend. He was Antony van Leeuwenhoek, inventor of the microscope and other optical devices. It was he who handled Vermeer’s estate when he died in poverty at age 43. There was no camera evidence left behind. My guess is that van Leeuwenhoek took back his valuable lens.

Best regards,

Robert

PS: “Vermeer achieves uncannily photographic effects while painting in a way that is often locally imprecise and where focus is sometimes lost. The camera served as a composition machine. Stillness, reticence, hesitancy and psychological ambiguity are qualities not unrelated to his use of the camera obscura.” (Philip Steadman)

Esoterica: Girl With a Pearl Earring is also a girl with an open mouth. There’s a soft transition from cheek to lip — sensuality, breath, a glint of moisture. “The Girl” is in the Mauritshuis in The Hague. When I was last there she was to the right by the stairs going in. She’s drop dead beautiful. I’ve asked Andrew to put up some valuable Vermeer material and further links.

Johannes Vermeer (1632 – 1675)

The Art of Painting — (RG notes) I’ve always thought this painting to be the most telling of Vermeer’s work. The painter with his maul stick works in the standard manner in front of his model. Is this the ploy of a painter who feels guilty about his secret shortcut? A few notes: The map: It’s true in distances and dimensions to extant maps. If traced by camera obscura, the map would have to be reversed. The artist’s complex jacket: To my eye this shows the random effect of a true projected image. The rolled down boot socks: These also appear to me to be the work of a tracer, rather than that of a painter such as Franz Hals, who worked directly from life and understood and worked the mysteries of clothing in a more intuitive manner. Take a close look at the chandelier: You’ll see random spotting without the mechanical understanding that comes with sorting this sort of thing out with drawing. Elements and images beautifully rendered without benefit of theory.

Plan of Vermeer’s room with viewpoints (small circles) marked for six paintings: (a– The Girl with a Wineglass) (b– The Glass of Wine) (c– Lady Writing a Letter with Her Maid) (d– Lady Standing at the Virginals) (e– The Music Lesson) (f– The Concert) The diagonal lines mark the extent of what is visible in each picture. The heavy lines at the back wall mark the widths of the six projected images: each is the width of the respective painting. This drawing is taken from Philip Steadman’s book Vermeer’s Camera. In this particular drawing the lens position is shown moved around in a small area to accommodate the various paintings produced. A ten-centimeter uncorrected lens has been suggested and this element would produce paintings to the sizes they actually exist. Vermeer worked in a tiny darkened cubicle between the lens and the wall. Steadman’s book is packed with a wealth of understanding of both sides of the Vermeer question. An excellent website that summarizes these and other findings is at www.vermeerscamera.co.uk Further material can be found at the National Gallery of Art web site.

Girl with a Pearl Earring — This may not be “Griet” (Scarlet Johansson) as depicted in the movie. I like to think her as one of Vermeer’s daughters. He had eleven kids — perhaps ready and inexpensive models for a guy who was perennially broke. There are several of Vermeer’s paintings that appear to me to be directly painted without benefit of a traced and reversed drawing. This is one of them. There are apparently no signs of a preliminary drawing anywhere on the canvas. The design, the simplicity, the simple palette, all suggest to me a direct sort of experiment. And, as Betty Edwards suggests, there’s value in working up-side down, and this pearl of a painting seems to have some of those qualities. Fellow Dutchman Vincent Van Gogh was fascinated by it — at a time when Vermeer had hardly become popular. “This strange painter’s palette,” he said in amazement, “consists of blue, lemon yellow, pearl gray, black and white.”

Time saver

by Robert Turenne, Montreal, Quebec, Canada

I did a research project on Vermeer and his possible use of the camera obscura in University. When I presented in class, it lead the group to conclude “and so what… these are still incredible paintings!” Whatever the method, be it talent or a projector, there is more to painting than tracing lines. Much more. Further, I have been trying to democratize the use of projection devices as painting tools for a while. But although the public doesn’t seem to mind, the painting community is the real show stopper. I get a lot of reactionary comments from peers, gallery owners and teachers alike. I use a projector often, (attached to a computer) especially when some of the details I plan to introduce in a painting would consume most of the time for some of the impact, but still require careful treatment.

Book catches atmosphere

by Dave Edwards, Blyth, England

For a few weeks now I have been reading about Vermeer. It all started when I read a novel called The Pearl Earring, a fictional account of Vermeer’s servant who may or may not have posed for the painting you mention and publish. It may not be 100% accurate but it certainly caught the atmosphere of his home and studio and prompted me to go on the internet in search of more information. The other day I was reading about how Vermeer may have used a camera obscura to assist him in accuracy and here you are giving us loads of fascinating details about it all.

Missing leg mystery

by Gail Griffiths, Monmouth, NJ, USA

In Vermeer’s painting, The Art of Painting, there is something else that I get a kick out of — it is the fact that the left leg of the easel was decidedly left out by Vermeer. An old chum of mine who paints a Vermeer once a year, acquainted me with the art of this master of light.

(RG note) It’s easy to get lazy and not think about things when one is working from a projected image. To the eyes of most people the easel leg should appear a bit to the left of the leg of the artist’s stool. When one draws or paints directly from life these sorts of lineups are generally noted by our stereo vision and compensated for in the planning stage. The projecting artist, no matter how brilliant, must always keep his or her mind open for visual “truth.” He or she may or may not wish to honour this truth, but that’s another matter.

Evidence in the paintings

by David Lloyd Glover, West Hollywood, CA, USA

Most notable clues to Vermeer’s use of a projector would be the highlights which form into round dabs or circles. A lens being spherical reads light reflections as circles. You may have heard the photographic term of “circles of confusion”. This occurs when there are a number of highlights say bouncing off a chandelier, especially when outside the lens’s depth of field. It appears that Vermeer employed those circles in some of the highlight details. When drawing directly from life, your eye does not reduce the highlights to pure circles because or depth of field changes every time we focus on a different part of our model, subject or scene. Although no camera obscura contraption was ever found in Vermeer’s studio, the evidence seems to be in the paintings themselves.

Canaletto projected

by Grace Cowling, Grimsby, ON, Canada

Canaletto also used this device quite blatantly on Italian streets to capture the architectural detail he was so famous for. Can we assume that he was above embarrassment or comments from lofty critics, even curators, and simply used what worked for him? There are arguments against high realism, ho-hum representations, etc. but these old eyes see a generous amount of decadence garnished with arrogance. Yes, and a small turning about to representational art that quiets the soul and offers solace from the present world. There will always be those artists who feel it is their calling to portray our timeline for those who come after. But aren’t there enough cameras out there doing a commendable job of recording such?

Giovanni Antonio Canal or Canaletto (1697-1768)

Canaletto using a portable camera obscura. His paintings are so accurate that researchers studying climate change have used them to estimate the rate of change in the water level of the Venetian lagoon.

Part of our lives

by Susan Burns, Atlanta, GA, USA

A painting that evokes a feeling is a successful painting. Feeling cannot be achieved with technology alone. If 10 people projected and copied the same image, we would have 10 different images (10 different feelings). Even in photography, the feeling comes through, I always get compositional surprises when I use my projector, and sometimes it gets me out of a rut, but an artist still has to have a vision to make a painting complete. I told a friend that paints abstract figures about projection and she at first thought it was a sin against art. But now she is newly motivated and has taken it one step further with technology, by shooting a digital photo and turning it into a mini work of art on the computer. When you enlarge or shrink something, it takes on other qualities. Technology is a part of our lives.

Black holes

by Fern Louise Shimmel, Santa Rosa, CA, USA

Vermeer’s work has always made me jealous of the accuracy of his details. I never thought I could come close. Now we are learning why. I have used photos for years, both in classroom teaching and at home. They are excellent for teaching perspective — something that many artists cannot see. There is a trick in painting from photos…they must be your own, as you need to remember the details in areas too dark to show in the photos. Black holes are what many paint when copying from others’ photos or their own until they learn this trick.

Amazing quality

by Pamela Simpson, Woodstock, CT, USA

Your letter brought to my mind the quote, “You can borrow all the flour you want but you have to bake your own bread.” (author unknown). Vermeer might have traced his interiors but he still had to paint them. Of the paintings you showed us, I think the best one is the one that shows no sign of being traced. It must have been very difficult for him to get any painting done with 11 children around; we have 6 and it is hard enough with that many. Traced or not, his work has an amazing quality to it.

Controversy

by Kimber Scott, Albuquerque, NM, USA

I would like to point our readers to the following information regarding the reported use of the camera obscura by the Old Masters, including Vermeer. It is quite a controversy and, seemingly, the use of the machine is without proof. Read the article published by the Art Renewal Center: Knowledge without Substance — Review of David Hockney’s Secret Knowledge by Kirk Richards.

(RG note) Several artists wrote to remind us of Secret Knowledge, Re-discovering the Lost Techniques of the Old Masters by David Hockney — and of the controversy surrounding it. Another useful page published by the Art Renewal Center is Hockney Completely Refuted, by Fred Ross.

Previous input on our site on the David Hockney book:

— David Hockney’s secret knowledge by Laurie Boese and myself.

— David Hockney by Zoe Pawlak

— David Hockney’s “secret knowledge” by Carol Lopez and myself

With regard to Ingres, in his particular case it looks to me that he did his drawings without the benefit of a lens.

If you like it

by Julie Rodriguez Jones, San Pablo, CA, USA

Recently, my colleagues in the International Association of Astronomical Artists had a similar discussion about how we create our art. Many are scientific illustrators and use a variety of digital and sophisticated CG techniques while others of us are digital “purists” and create freehand “fine art” works while a few use paint and brush. Are those who use CG techniques any less competent or skillful? Some of the works they create are stunningly beautiful, while using sophisticated processes. We have decided that until the public knows more about how our works are created (or until the different styles of digital art are better defined) the bottom line is, does our intended audience like what we produce and want to acquire it? In all cases, the answer is yes! So academic discussions aside, if you like it or it evokes something within you, that is what is important.

Projects minimalist work

by Marc Robert North, Vancouver, BC, Canada

I first encountered this dilemma at art school when it came to representational painting. I decided that if I’m painting, why spend a great deal of rare and precious time drawing (and re-drawing) when I can wheel out the ol’ opaque projector and get the image down and make the ‘painting’ mine. Having said that, I admire those who can take the time to do fabulous drawing. I, myself, am very talented at representational drawing and I do it from time to time but its not ‘my thing.’ My thing is colour non-representational minimalism which you would think wouldn’t require projected images. But what I do is draw my images on paper in pencil using French curves, templates, rulers and a bit of free hand. Then I project it with an Artograph Super Prism opaque projector onto the canvas and then translate that image free hand. This keeps me in the loop and keeps the pieces from looking too perfect.

Illuminated oil painting |

You may be interested to know that artists from every state in the USA, every province in Canada, and at least 115 countries worldwide have visited these pages since January 1, 2003.

That includes Ted Berkeley of Portland, Oregon who was one of the artists who drew our attention to David Hockey’s book, and then wrote, “I’m typing this letter, snowbound at home, and the view from my window could be Breughel’s Hunters in the snow, hills, trees, birds and all.”

And also Barbara Loyd who wrote, “Why can’t we admire Vermeer and refrain from analysis of him or his art? Most artists use any tools available at their time. The use of a camera obscura does not diminish the value of any artist’s work.”

And also Janet Warrick, of Chicago, Illinois who wrote, “While a crutch works well in holding one up and gets you around nicely with a broken leg, a crutch in art does nothing to further an artist’s understanding, and I believe will only hinder further growth.”

And also Karen Rebernak who wrote, “In light of the recent release of the movie about Vermeer, I think it’s a little bizarre that you chose him for the subject of your email today.”

And also Jerry Waese who wrote, “Due to a passing resemblance to the Vermeer Girl, someone photographed my daughter beside a poster and I came up with this.”